An intentional mess

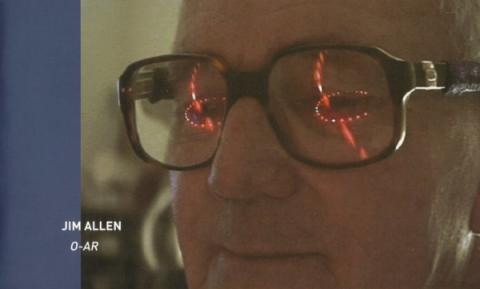

Jim Allen, O-AR1, St Paul Street Gallery 2007

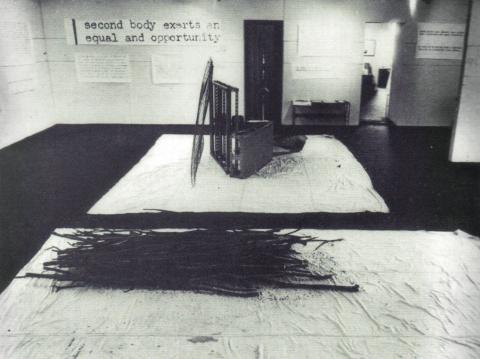

Jim Allen’s mess of printed texts, calico drop-sheets, children’s work, manuka (ti-tree) branches and metal grids is both a re-staging and a re-construction of the artist’s 1975 installation O-AR1. It is useful to ask, what are the effects of re-making and re-showing the work now, 30 years later? It is an important gesture, but why? How is it important?

In the first instance it is important historically, because of the leading influence Jim Allen’s thinking and practices had in the Auckland art scene in the 1970s. He is regarded as an important figure in what we can now call the history of New Zealand’s conceptual art movement during the 1970s – a movement known in New Zealand and Australia as Post Object Art. He was influential through his role at Elam School of Fine Art where he headed the sculpture department at the time, affecting the thinking of a generation of young artists and being the catalyst for a number of key overseas artists coming to live and work in Auckland for short periods. His own art practice was also influential in that he is credited by Robert Leonard with creating New Zealand’s first environmental sculptures following what he had experienced during a sabbatical in Britain, Europe, the United States and Mexico in 1968.

The O-AR1 installation is characteristic of the artist’s 1970s practice for its juxtaposition of materials, objects, images, words and phrases, in what seems like an unexplained or incomprehensible arrangement. This structure of the installation, what could be called an open ended situation, was intentionally a mess (to use Jim Allen’s phrase) to encourage viewers to participate in connecting and interpreting the parts. Allen was interested in systems, particularly the relationships among the various interrelated elements of a system and the ways systems become regulated through each part communicating with the others. This interest meant that he became less interested in a managerial regulation of a system to create an outcome and more interested in creating complex situations where many parts came into contact with each other and were invited to communicate, generate feedback about their own state in order to arrive at an outcome through the interaction. This approach in the gallery echoed Allen’s approach to teaching at Elam in the same years, which was non-directive and focused on open-ended discussions about work-in-progress and ideas that would lead to new combinations of thought and new collaborations between the participants (artists, students, lecturers).

Re-making and re-showing O-AR1 is also important for the reason that it sheds light on the continuity of this mode of working in a strand of conceptual, and critical, contemporary art practice today. It is possible to see very similar approaches in the work of two new generations of artists who should not be seen as his descendants, but as his contemporaries – thus showing that Allen’s 1975 mode of working still has currency, is still useful and provocative. What artists such as et al., Judy Darragh, Denise Kum, Simon Denny, Seung Yul Oh and Eve Armstrong share with Allen is the playful disruption of easy answers, or immediacy of interpretation, through the seemingly chaotic juxtapositions of objects, materials and sometimes images and texts within installations. In each case the artists create situations that invite a very active participation by viewers in a communication exchange with and between the various elements. In each case the artists present incomprehensible situations, sometimes with a playful tone (Darragh) and at other times in a menacing register (et al.).

At the risk of seeming over-determined, re-staging O-AR1 now is also important politically. Given Allen’s interest in systems and given that conceptual art was a part of the post-1968 legacy of challenging unitary authority, the work’s open-endedness and its insistence on disrupting conventional interpretation can be seen as a form of resistance and as a manifesto for the unfettered imagination.

In an age of political dogmatism, widespread xenophobia, ethnic intolerance, resurgent nationalisms and paranoid fundamentalisms, any social-cultural forms that remind us of the values of engaging with the incomprehensible, reflecting on the complex and participating in open-ended situations where the outcomes are unknown, have the potential to unlock our minds from habit and unleash the imagination. Perhaps, at times the discomfort of encountering an art installation that seems to attract and repel at the same time, which requires thought, that does not yield up easy answers or coherent feelings is too much.

Answering the demands of such art with thought and discussion is a small price to pay for the preservation of the life of the unfettered imagination. Imagination ranges across the chasm between the safety of what we know and understand to new understandings that expand us and our capacity for citizenship. Jim Allen’s open-ended installations are a figure of the potential for connection between disparate parts. At the same time, to see this potential, and not be blinded by our own lack of understanding, requires that we exercise our imagination and play, or grapple, with the elements before us.

O-AR1 in the 1970s was encountered as an over-saturated environment. There simply seemed to be too much going on, too much to grasp or figure out. This is an effective strategy for inducing a sense of incomprehensibility – similarly this sense can be achieved by giving the viewer too little information or stimulation, and Allen’s O-AR2 later that year tended towards that pole. However, with too much material and with so much complexity it is the viewer’s response to their own bewilderment that is most interesting. O-AR1 may not seem over-saturated to many viewers today given that we live in a media saturated age, and that many art viewers will have also seen decades of very complex environmental installations. However, its various elements are not easy to decipher or interpret even today, and it is likely that viewers will still move around the installation with a growing sense of incomprehension. Being too much or too complex to work out is the contemporary challenge the work poses. It posed this challenge in 1975 and it is likely to be just as fresh a challenge in 2007.

Try reading the large text fragment on the wall: ‘second body exerts an equal and opportunity.’ Read it out loud. It’s nonsense. But it is also partly recognisable. Some might recognise something of Newton’s maxim about the second body exerting an equal and opposite reaction. But the phrase is broken and substituting the word ‘opportunity’ at the end of the phrase makes it neither a fragment of another sentence nor a new phrase – it makes it nonsense. The only way of making sense of this is to see the logic in the tactic, not in the phrase itself. Jim Allen’s tactic is to allow something recognisable within a phrase that makes no sense at all. It is a tactic that tries, as he says, to ‘create a gap between the definitive statement and the residue of meaning.’ That is, he is trying to create a gap between the fragment we are presented with and the complete meaning that we might have expected. As a tactic it is not just about these words, this meaning, that gap. It is about the idea of a gap between an expected meaning, a simple answer and the incomprehensibility of the material we actually have in front of us. For Allen, the moment we recognise the incomprehensibility of the phrase is actually the moment of opportunity – to be creative, to be self-aware, to realise that being attached to certainty is not always the most progressive thing. Now, at this moment, seeing that he has inserted the word ‘opportunity’ at the end of the broken phrase makes sense – not as a sentence, but as an idea. For Allen, incomprehension arising from broken continuity is an opportunity. As such, Allen’s tactic sets up a metaphor for the breaks in continuity and resulting incomprehensibility all around us and asks us how we are going to respond to that incomprehensibility. Will we engage with it, participate, or walk away from it, seeking comfort in simplicity and quick answers? Allen will hope that we choose to engage. Allen hopes that by confounding and confusing us with a lot of material that is seemingly unconnected he will promote ‘a climate of enquiry’ within and between us. We know this because in 1975 O-AR1 was not just an installation, but also a discussion.

In 1975 when Jim Allen’s installation was first made and shown at Barry Lett / RKS Gallery which occupied first floor rooms on Victoria Street West, Auckland, the art community was relatively small. There were less than a handful of dealer galleries, no artist-run spaces or independent project spaces and very occasional art reviews in The Listener or Landfall. The Auckland City Art Gallery’s projects programme was the equivalent of what might be found now in places such as Artspace, Te Tuhi Arts Centre and St Paul Street Gallery; and the one art school, Elam, played a vital role as a major generator of new conceptual work and as a host to international artists.

Interestingly while Allen’s teaching practice at Elam was pointedly non-directive – a frustration for many students – he fostered a climate of enquiry and exchange through regular group discussions in his office, in studios, workshops and galleries, about work-in-progress and ideas. He stimulated people to bring what they were working on into a situation of exchange whether they were his students or the artists from overseas that he hosted as lecturers and artists-in-residence. These situations often led to new working relationships and projects that could only have been realised by people joining in, whether as active and creative participants, or as assistants.

The scene was both dynamic and fledgling. Nevertheless it was difficult to get feedback about exhibited work. In background notes on O-AR1 Allen recently wrote that ‘many exhibitions simply disappeared without trace. Curatorship as we know it today, and art networks, both national and international, were at a rudimentary stage. Critical discussions, so much a feature of exhibitions held in public art galleries today, did not take place.’

Jim Allen brought his teaching ethos and his concern about the lack of dialogue in the art scene into O-AR1 and established a situation where feedback loops were a part of the art work. O-AR1 is one of several installations where he attempts to achieve this, in several ways. When people received invitations to O-AR1 it was to two exhibitions: O-AR Part 1 at Barry Lett / RKS Gallery in July 1975 and O-AR Part 2 at Auckland City Art Gallery in November of the same year. One implication for people who received this double exhibition invitation was that they would have to carry something over, in their experience, memory and expectations, from Part 1 to Part 2. In this sense, Part 1 was an open situation; it was not closed off to further, later interpretation; it was not finished.

Jim Allen was careful to qualify the open-endedness of this relationship between Part 1 and 2. He pointed out that he did not see Part 2 as a ‘sequel’ to Part 1 and that he was not the sort of artist to work in series. If it was not a sequel, Part 2 did not complete the ‘incomplete’ Part 1; and if 1 and 2 were not elements in a series, they should not be read as equivalent to each other. Allen intended the two installations to be seen as different situations but as one work – in this sense Parts 1 and 2 could be read as two complex situations with the potential for a feedback loops between them.

A further aspect O-AR1 where Allen’s interest in feedback loops is evident is the gallery discussion that he staged involving himself, Bruce Barber, Wystan Curnow, John Lethbridge, David Harre and Billy Apple. The discussion, which took place in the installation at Barry Lett / RKS Gallery on 31 July 1975, was recorded and a transcript produced. Each participant was invited to make corrections or additions by hand on copies of the transcript and the resulting bricolage of typed text, crossings-out, additional comments and photographs of O-AR1 was published as the show’s catalogue. The openness of Allen’s installation is at times bewildering, offering confusing and incompatible juxtapositions rather than giving up a coherent story or set of meanings to a viewer. However what is so appealing about the catalogue discussion is the directness of the participants: the directness with which they engage with the elements of the installation, the directness of their discussion with each other, and the directness of the catalogue’s typed, hand-written and crossed-out representation of their participation in the situation which is O-AR1.

While some of the elements of O-AR1 may carry with them the aura of a past decade, the installation’s structural properties and the deployment of complexity and incomprehensibility to make us aware of the ever-present gap between what we encounter in the world and what we think we know, ought to be as resonant and feel as pertinent today as they were in 1975.

Previously published in Jim Allen O-AR, edited by Leonhard Emmerling, St Paul St, AUT, 2007