Walking with letters

Parekowhai, Reynolds & Pule

Since the middle of last century one of the strongest underpinnings of the word in art in New Zealand has been literary. Literature and citation are evident in the works of Michael Parekowhai, John Reynolds and John Pule. The Indefinite Article was one of several Michael Parekowhai works in the 5th Asia-Pacific Triennial at the Queensland Art Gallery; poetry works on paper and oil paintings on canvas by John Pule were on show in Brisbane’s new Gallery of Modern Art, also as a part of APT5; and earlier in the year, John Reynolds’ Cloud was installed in the Art Gallery of New South Wales as a part of Zones of Contact, the 2006 Biennale of Sydney.

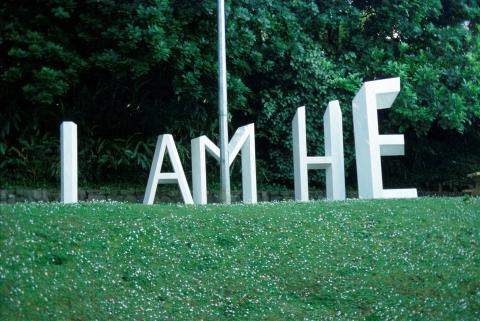

Michael Parekowhai was born in Porirua near Wellington and is of Nga-Ariki/Te Aitanga-A-Mahaki and Rongowhakaata and European descent. The Indefinite Article, 1990 (Collection of Jim and Mary Barr, Wellington) is one of Parekowhai’s very early work and spells out ‘I AM HE’ in a set of three dimensional cubist letters in an ironic critique of Colin McCahon. As illustrated here, photographed in the grounds of Elam School of Fine Art, the letters march out across two abstracted green planes forming an horizon line between them and as such the picture not only references McCahon’s words, but also his frequent deployment of text with landscape.

The Indefinite Article plays on a multiplicity of possible readings. The title points to fact that in the Maori language, the word ‘HE’ is the indefinite article ‘a’ or ‘an.’ In so doing it also points to the way the word alludes to Maori and Pakeha identity are implicit in each other: ‘HE’ is the triumphant Maori exclamation at the end of many haka just as it is the English personal pronoun. Parekowhai does not ask us to choose between these meanings, but entertain them both. Despite Parekowhai’s own mixed parentage he is mostly described as a Maori artist, so his sense of humour is evident when he points out that the letters ‘I AM HE’ only lack ‘C’ and ‘L’ and simple re-arrangement to spell his own name: ‘MICHAEL.’ As ‘C’ and ‘L’ are not found in the Maori alphabet, this observation again suggests that identity and voice are necessarily plural. Parekowhai simultaneously asserts and displaces his Maori identity, thus expressing that sense of ambiguity felt by many Maori with Pakeha ancestry – territory explored by a number of young Maori artists in the 1990s.

The work’s word play goes further, and through a double reference to Colin McCahon cements the link between the word, identity and the complexities of translation. Firstly, there is a reference to McCahon’s Victory over Death 2, 1970 in the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Visually bolder than anything McCahon had produced before, Victory over death 2 opposes a questioning and doubt-filled 'AM I' with a bold and assertive 'I AM'. With the former phrase painted black on black it is only in the physical presence of the painting that the viewer becomes fully aware of its questioning. Parekowhai’s ‘I AM’ clearly references the bold assertion in this painting.

Secondly, his addition of ‘HE’ to McCahon’s confident declaration is on the one hand a sly reference to the doubting black on black ‘AM I’ in Victory over Death 2 but it also points to a similarly troubled word painting in the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery collection in New Plymouth: Am I scared, 1976 which spells out in white on black ‘AM I Scared Boy (EH).’ Parekowhai thus shares an affinity with McCahon’s contra positioning of belief followed by doubt, which is how McCahon sequenced the two: doubts follows and lingers. But more than this Parekowhai critiques McCahon. His citations lack McCahon’s gloomy foreboding and aloofness, and in turning McCahon’s conspiratorial or approval-seeking ‘EH’ into the exclamation ‘HE’ distances himself from the father of New Zealand modernism.

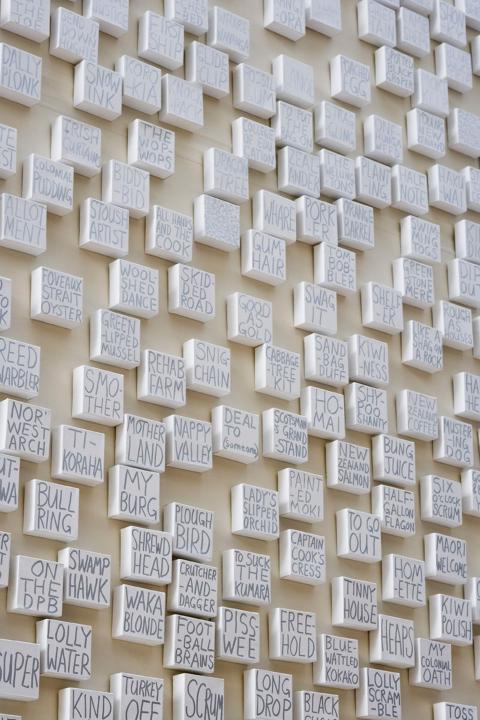

It is possible that every New Zealand artist since McCahon wrestles with his ghost in some way when using words in their art. John Reynolds seems not to worry about haunted houses, but like McCahon, he has made a picture for people to walk past in Cloud for the 2006 Biennale of Sydney. Comprised of nearly 7,000 white canvases ranged across the tall long wall on the right, just inside the AGNSW lobby, each 100x100mm block has a text drawn in capital letters with silver enamel paint markers. Walking past the work rewards the viewer with shifting visual effects. The silver on white gives the work as a whole a spectral and fugitive quality which is crucially animated by the nature of the lighting source and the proximity and movement of the viewer.

The work is also a walk of a conceptual kind. Reynolds transcribed words from Harry Orsman’s Oxford Dictionary of New Zealand English, a regional dictionary of ‘New Zealandisms’ which comprise a small, yet significant, part of any New Zealander's total vocabulary. Orsman's book provides an historical record of New Zealand words and phrases from their earliest use to contemporary times. Thus it illuminates New Zealanders’ separate identity, their regional diversity, and signals their membership of a worldwide community of English speakers. In Reynolds’ word work most of the book's 6,000 or so headwords and a selection of the 9,300 sub-entries are accumulated. He recalled that ‘the pedestrian toil in the work's production recalled the ‘hard yacker’ of Harry Dean Stanton, walking speechless under a big sky, in the Wim Wenders film Paris Texas.’

Drawn in metallic silver on primed canvases and randomly dispersed on a billowing scale, the words condense and evaporate. LOLLY WATER, ON THE DPB, SWAMP HAWK, WAKA BLONDE, TO SUCK THE KUMARA, HEAPS, HOMETTE, SIX O’CLOCK SCRUM ,MY COLONIAL OATH, DEAL TO (Someone), NAPPY VALLEY, SHYPOO SHANTY, MUSTERING DOG, CABBAGE-TREE KIT, GREEN-LIPPED MUSSEL, REHAB FARM. Walk up close and these speech fragments loom and register; step back and they haze, becoming a cloud of white, silver and grey.

Just as the visual form of the work shifts in and out of focus, the meanings of many of the words and phrases are fugitive. Like distant and indistinct voices, or a strange dialect in a familiar language, a precise sense of meaning has faded from contemporary memory or usage. Equally baffling, or intriguing, is any sense of whether the artist has clustered, strung or grouped the blocks in any order one to the other, to set up chains of meaning and relationship. One suspects not, but many viewers were observed pondering this very question in an exploratory way. Perhaps, as Reynolds suggests, they are a clamour of New Zealandness; a Long White Cloud of kiwi expression. If so, they are a clamour that spans decades and a multiplicity of contemporary identities. Collectively they offer clues to stories unknown and memory aids stories that can be recalled.

John Pule is a story-teller: stories of migration, of dispossession, of alienation, of belonging, stories of how the savage Other resides in each one of us. While his artistic forebears McCahon and Hotere inscribed the poetry of others into their paintings, John Pule clusters and weaves drawing, printmaking and painting around and through his own words. Like Reynolds and Parekowhai he deploys words to multiply meanings and confound interpretation or translation.

Beginning his career as a poet and novelist, John Pule expanded his practice in the late 1980s and early 1990s to include drawing, printmaking, painting, performance and film. Born on Niue, Pule migrated to Auckland, New Zealand, at the age of 2 in 1964. The experiences of migration and dislocation, as well as the exploration of his Niuean cultural heritage, continue to act as catalysts for Pule's practice. He sees himself as an outsider to both cultures – caught in a dichotomy between contemporary European New Zealand and traditional Niuean culture.

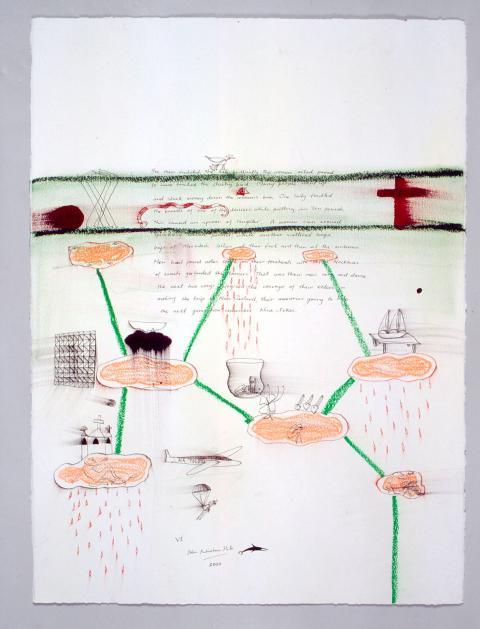

During the 1990s Pule’s art works were based on the structural tradition of the hiapo (Niuean bark cloth), but his more recent works have largely abandoned its linear formality. In recent years his stretched canvases have been populated by blood-red and grass-green cloud shapes that carry pockets of visual narrative. Recurring symbols and motifs in his work include hybrid bird-like lizards, botanical motifs, birds, the Christian cross, Pacific church buildings, aeroplanes, broken aeroplanes mounted by two-headed monsters, ambulances, decapitated heads, fantastical creatures breathing fire, skulls, sex acts, island silhouettes, drifting island-clouds, and his own poetry.

A recurring motif is the vines of the ti mata alea (Cordyline tree), which in Niuean culture is believed to be the plant from which human life originated. By depicting this vine motif Pule represents the origin of his people, their foundation. This imagery holds great meaning for Pule, whose family brought native Niuean plants with them to New Zealand to establish in the soil of their new home, a common practice of Pacific cultures. This mixing of soils, this attempt to find anchorage, is visible in his paintings audible in his poetry, but so is its fundamental failure. In many of the recent works where clouds have replaced islands and the hiapo grid structure has all but evaporated, failure to connect is as much a motif. In the poetry print VI Untitled, 2000, instead of vines, there are tears falling from delicate pink clouds. The failure evident in this and other similar works is that of the Diaspora, that of all displaced, to find peace. In X Untitled, 2000 Pule writes:

why ask those who are old

girths as strong as the kafika trees

to follow their sons and daughters

tricked by a postcard moon?

Bloody is the shift

tearful is the move

sadness to those who know other lands

happiness for those who wave them on

Part of Pule’s strength lies in his ability to reference traditional motifs without being tied to notions of origin and authenticity that have played into the hands of those who can only see the exotic Other in the Pacific. Pule’s words and iconography are slippery, on the one hand referencing the collective memory and contemporary consequences of the colonisation of the Pacific and the broader issues of displacement, migration and return, and on the other hand creating personal and obscure motifs that defy interpretation. For the non-Niuean viewer there is no access to the specific content of these works, but even for Niueans many of the references are so deeply personal that translation and cultural accommodation are equally challenged. In Pule’s case this inaccessibility can be understood as a deliberate resistance which points up the various power dynamics between the creators of contemporary Pacific art and its various consumers, including those in galleries seeking translation. Pule’s obfuscation marks the limits of cultural exchange.

Is this a deliberate strategy shared by each of these three artists, each in their own way? Pule underscores the incomprehensibility of Pacific displacement; Parekowhai complicates notions of Maori identity in ways that challenge New Zealand’s current attempts to deal with cultural diversity; and Reynolds demonstrates that words, the stuff of our shared language, and their meanings are fugitive. Each presents the viewer with such plurality and complexity as to mark the limits of interpretation and translation. In these word works, as slippery as eels, there is something to be gained from becoming aware of what we don’t know and can’t understand.

Originally published in Artlink, vol 27 # 1, pp46-49.