Rob Garrett

Curator

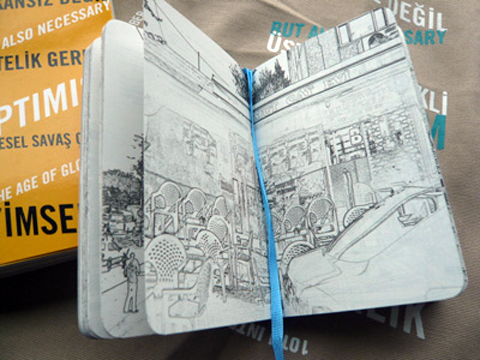

Reasons for optimism

10th Istanbul Biennial, 2007

Where can you leave luggage unaccompanied these days? Not at airports or rail stations, but in art galleries. After transiting through a number of airports to get to Istanbul, I had numerous recorded security warnings about left luggage echoing in my mind. So I was amused to find Russian artist David Ter-Oganyan’s installation, at the portside biennial venue Antrepo No3, getting its hooks into me.

Secreted throughout this exhibition hall were eight “horrible and comical” objects, from his series This is not a bomb (2006-2007). Made from everyday things, bits of clockwork and wires, Ter-Oganyan’s look-alike bombs test our powers of observation and play with two facets of improbability. Firstly they address the improbability that anything will be hidden in an art gallery where visibility is everything; it was intriguing to observe very few people seemed to notice these bombs, even when they were standing or sitting right next to them. Though they were tucked under stairs and in corners, they were not really hidden. Nevertheless, many people, like me probably did see them. What did we do? Nothing; the second improbability is that gallery goers will take action in response to artworks. These objects collude with our ability to suspend our normal behaviour and beliefs in art galleries. To all intents and purposes they look like bombs; why do we suppose they’re not, or act as if they’re not? Is it because the gallery is one place where the everyday is evacuated of the real for the sake of ‘looking like’ and ‘being about’? Ter-Oganyan’s bombs interrupt the unconscious separation between the real and art.

I encountered these thought-bombs while attending the opening of Not Only Possible But Also Necessary: Optimism in the Age of Global War,10th International Istanbul Biennial, curated by Hou Hanru. Twenty years since the event was founded, Hou aimed to refresh the format and have the biennial emulate the city’s sprawling, fragmented and dynamic energy, while referring to its current situation in a globalising world and an expanding Europe.

In contrast with the rather dystopian Arsenale exhibition curated by Robert Storr for this year’s Venice Biennale, Hou declared that optimism is “not only possible but also necessary.” Both curators had selected artists who were engaged with pressing socio-political, economic and militaristic issues of the day; but while Storr’s selections told us what we already know – the world is in a bad state – Hou’s choices tended to come across as forward-looking and therefore more thoughtful.

The biennial stimulated my mind, and the city overloaded all my other senses as I explored and reached exhaustion during five days of 30 degree heat. The Beyoğlu, Cihangir, Cukurcuma and Tünel districts that I mostly frequented are bustling and cosmopolitan. Everywhere street vendors offer grilled corn cobs, glazed salty bread, lottery tickets, honey drenched sweets and cooked fish heads with lemon and herbs. Down side and back streets there are buildings and activities, like a carpenter’s workshop, that seem to have changed little in centuries, while nearby a chic global brand has its new storefront.

Turkey currently faces considerable challenges as it seeks acceptance by the European Union - incompetence and corruption, inequities between rich and poor, and though the free flow of information has improved, there remain challenges to free speech in the rise of a reactionary secular nationalism. In this context, democratising propositions and calls for a civil society are timely. One such was the biennial’s Nightcomers programme. During China’s Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 1970s, the ‘lower class’ was encouraged to post their critiques of the elite in the form of ‘Dazibao’ (a journal or poster with large letters). Hou notes that at this time “street corners became public forums. In spite of totalitarian propaganda, this approach showed a form of radical democracy.” He wanted a similar, but contemporary, equivalent of this for Istanbul.

For Nightcomers five local curators were invited to select over 150 short video works from those which came in after an open call for submissions from the public. These were projected onto vacant sites, walls and street corners across the city. Hou claimed that for the first time in the history of the biennial “a real open participation of the public has been made possible so that thousands of people living in areas without access to ‘high culture’ can have direct contact with contemporary art”. To this end 59 public sites for the nightly screenings were researched, selected and documented (in a gorgeous white pocket-sized book) by the Dutch artist couple Bik Van der Pol (Liesbeth Bik and Jos van der Pol) who had been resident in Istanbul for the preceding five months. Venues included the top of the old Galata bridge, which had suffered a fire and had its middle section removed; a densely populated public square with ice cream stall, mosque, fountain and cafes; a vacant wall at a crossroads; and a bus station on the periphery of the city, with public toilets and a public square where “lots of people pass, wait, hang around, go to the toilet and wait a bit more”.

Turkish artist Esra Ersen’s video installation at the newly opened santralistanbul Museum of Contemporary Art touches on Turkey’s status within the economy and consciousness of Europe. Indentured labourers in Europe for many years, Turks now tenuously approach full citizenship through drawn out preparations for accession to the European Union. I am Turkish, Straight and Hard-Working (1998/2007) was first realised in 1998 when Ersen worked with a group of German secondary school pupils in Velen, outside Münster. The children wore Turkish school uniforms for a week and wrote down how they experienced wearing this different costume. Their notes were then transferred directly to the uniforms and exhibited in the school. The project was repeated in 2005 in a school in Teistlergut in Linz, Austria. Ersen’s engagement with “socio-political, economical, geographical contexts” was structured around her interest in potential – “either the potential of the people I work with or the potential of the space or the structure. So that I do not write down a script but rather let things flow.”

I encountered potential of another sort when I arrived at Antrepo No 3 for an opening party. I received a call: “Rob, where are you? We are going to eat fish. Come with us. Come now.”

And so an hour later I found myself on a small boat on the Marmara Sea, with Moscow gallerist Elena Kuprina and partner Maxim and three others, sailing past the Golden Horn, up the Bosphorus and back. Set before us on a giant platter were a grilled kalkan (turbot), the size of a tennis racket, and huge karides (shrimps), which we washed down with vodka and tomato juice.

We turned under the slender suspension bridge, which spans the Bosphorus and unites Asia and Europe, and glided past the beautifully lit city, past the baroque mosque Ortaköy Camii and palace Dolmabahce Sarayi. Suddenly the sky behind the city lit up with myriad flashes of sheet lightening as a storm approached. We reached shore and our taxis just as the torrential downpour arrived, drenching Istanbul and enveloping every vista in a glowing white shroud. It was a perfectly refreshing way to remember this city – sumptuous, spontaneous and surprising.

Dispatch from the 10th International Istanbul Biennial: Not Only Possible But Also Necessary: Optimism in the Age of Global War, September-October 2007 (with extra photographs). Previously published in Art News New Zealand, Summer 2007, pp80-82.