Marie Strauss

Mud, Coats and Cheese

MARIE STRAUSS'S POTTERY is located down a long stream-bounded and wooded track in the tiny farming community of North Taieri in New Zealand's South Island. Though hot and bright during the brief summer months, the farm where she works and finds her clay is mostly wet and lush, and often sodden and bitingly cold. It is a demanding environment. Appropriately her hand-built pots, with their weathered surfaces coaxed from successive firings and found materials embedded in the matt ash glazes, speak of endurance as well as hope. It does not seem over-determined to think about Strauss's pots in this way, for there is an evocative power of the objects she makes, and Strauss has said she wishes people to be able to identify with her pots. Strauss's forms seem to address the dilemma of knowing how to develop resilience for the forward momentum of living, when all around the fragility of life is evident. I am reminded of Yoko Ono's question when announcing her plan to re-stage her 1964 performance 'Cut Piece' in Paris in 2003: "I always thought I wanted to live forever, that I was one person who was not scared of doing so. But would I want to live surrounded by this world as we know now?"

Artists and their audiences are well aware that the way artists select materials and configure those materials in certain ways has the capacity to open and release the imagination. This is the foundation of the transformative power of art. In Strauss's case one could say that the particularities of her condition and her location have been filtered and abstracted through the process of making her pots. With the result that these objects, in and of themselves, speak of similar conditions and locations in a way that is accessible to many others. They are pots that are evocative of place, ways of living and states of being.

Shortly after immigrating to New Zealand from South Africa in 1993, Marie Strauss completed an Honours Diploma in Ceramics in Dunedin. Since then she has searched for and found her own voice in the craft. Her early work quite naturally revealed a strong attachment to Africa, "recalling," as Elizabeth Rankin and Martene Mentis have observed, "Venda clay pots and with surface decoration reminiscent of Shona textile design". Gradually pots emerged with a different but equally strong design aesthetic composed of elemental shapes with black and white designs. Their matt exteriors and glossy interiors revealed an affinity with the textures and moistness of her new location, and gave evidence of the influences of Danish and English potters--Hans Caper, Lucie Rie and Elizabeth Fritch. Many of these pots pre-figured approaches that were to mature in the pots featured here, with their weeping punctured walls, evoking the bright wetness of her new home. But something else emerged too, first as an undercurrent and then as a stronger vein in her work, which has become the dominant timbre in her voice. Namely an affinity with Strauss's own abiding passions: for building, clothes and food.

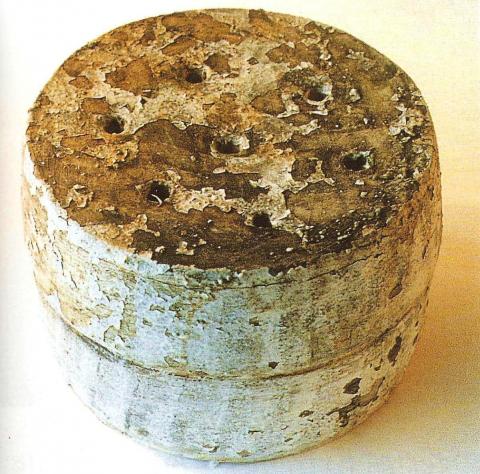

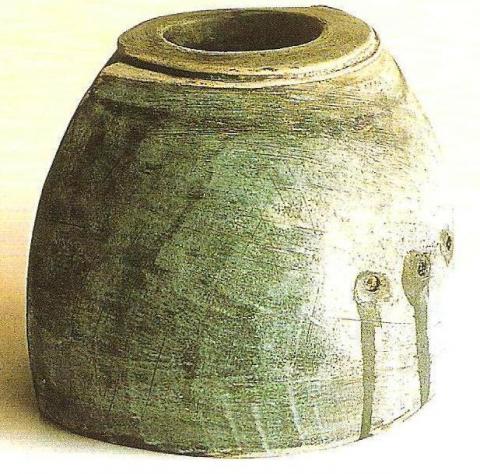

New Zealand is wet. Contrary to the unrelentingly sunny skies that radiate from every tourism publicity image of the country's landscapes New Zealanders live with constantly changing and often dramatic weather patterns that include a significant diet of wetness. Marie Strauss's pots reflect that the New Zealand outdoors is green, dark, damp and often muddy. The pots ooze: leaking surfaces and insides suggest the percolating of sodden ground and the weeping of the mud banks of deep-cut streams. They also have a heaviness in their squat and bulging forms that evokes the wetness of saturated earth clods; and the glutinous, muddy, hoof-pocked cattle races that braid the Strauss's North Taieri pedigree cattle farm. Strauss has intentionally deployed surface glazes that will fuse and drip to suggest the particularities of a land of mist and rain; and she created dark interiors to make them look like dank crevices, reminiscent of ponds and potholes.

Strauss betrays her passion for the materiality of things in the quality of the handling of the surfaces of these and later pots; and she is unafraid of getting her hands dirty. I have often visited to find her--sleeves rolled up, forearms glistening with oil, meat juices dripping off her hands and elbows, forehead dusted with flour where she has brushed her hair aside--as she rubs a giant slab of meat with oil, salt flakes and freshly ground peppercorns for one of her succulent and heady slow-cooked beef roasts. With a similar delight in what the inventive combination of materials will produce, some of her pots have been rubbed with sand or gravel from a freshly tarred road to suggest the texture of earth. Others have the texture of dry bark achieved by coaxing a glaze to peel, and still others have the patina of snow arrived at through the use of subtle white washes and the multi-fired layering of various slips and glazes.

It is not only a wet and richly textured land that she has evoked, but also a bright eye-squinting one. If the perforations in the pots are like oozing earth, they are also like tiny windows. They squint at one like the small perforations allowed in thick-walled dwellings where the heat and light of the sun are unbearable. New Zealand's bright light has given rise to architectural traditions in which deep eaves and wide verandahs are common, but there are few buildings that are as defensive as these pots are against the sun's radiant harshness.

They could equally be gun slits: the windows of those with a need to defend themselves. Strauss has overtly referred to the possibility of this interpretation in the title of her Fortress series. One can extend the metaphor further: they are sick; or, their mascara has run. They are grief-filled eyes; gunshot wounds; dribbling mouths. They also swell with the promise of future leaking--perhaps not leaking some hidden contents so much as leaking their substance. They suggest the possibility of liquefying; of returning to the muddy state that drying and the fire has arrested them from. Yet as if to resist this, and further emphasising their defensiveness, these pots posture as well grounded buildings: bunkers, hunkering down into the earth. I like this idea of architecture that tries to hide, ready to fend and enfold.

It feels as if Strauss wants us to walk around the architecture of her pots, thus tracing the proportions and disposition of their defences with our own motion; as if she wants us to fold our steps, one upon the other, in a circumnavigation that pulls us into a bodily mimicry, or repetition of the slow swirl of their folded forms. It is a movement that reminds me somewhat of the way a companion might come up behind and step around you slightly when helping you first into the arms and then into the folds of your coat or jacket.

The way I see it, these pots also fold in on something: perhaps on a protected core; something hidden. Or perhaps they enfold their own interior spaciousness; if so, it is an interior that both expands to force the folds outwards, and shrinks, or is compressed under the weight of the folding walls. This is breathing architecture; and in the folding of these pots I see Strauss's love of heavy winter coats. It is not too strong a phrase to say that Marie Strauss has a love affair with coats. She has a passion for them--textured, tailored, warming, structured and stylish. She hungers for them and develops a joyous and flamboyant jealousy for the coats of her friends.

The pots have an affinity with these coats in the weight and curve of the surfaces that wrap about each other. The clay's twining surfaces are reminiscent of robust woollen weaves folded, pleated and hemmed to succour a body against the cold and damp--fastened with a sturdy tie belt or chunky buttons. The affinity with coats is evident too in the attention Strauss pays to edging, like the carefully tailored cut of a lapel or fold of a buttoned cuff, or sculptural trimming of a felted edge. These edges are crisp without frailty; they are sturdy and have the weightiness that reassures your grasp, as if they will fill your hand with yeasty pride in the moment of grasping them around your body.

Lastly, I cannot look at these pale, folded, punctured and dimpled tumescent pots without thinking about cheeses: pale powdery rinds; ash dusted coats; melting interiors; veined middles; crisp and oily yellow skins. Strauss's pots feed the appetite for sweet, sharp, heavy, creamy satiety. I know there is something quite paradoxical in these deployments of ceramics to evoke the states of being one normally associates with muddy feet, hiding in a bunker, being wrapped in a warm coat and holding a round of ripe cheese. Strauss is quite aware of this and doubles the irony by having her pots betray the ever-present possibility that the forms will not hold; that they will leak and melt away in the throws of decay or flake and break into mounds of dust and shards. In this way, these pots address the most potent of questions: "How do we hold on to life when destruction and inner collapse are all about?" with both a warning of loss and the hope of present and future pleasure.

Previously published in "Ceramics: Art & Perception" December 2007, Issue 70, pp25-27.