Rob Garrett

Curator

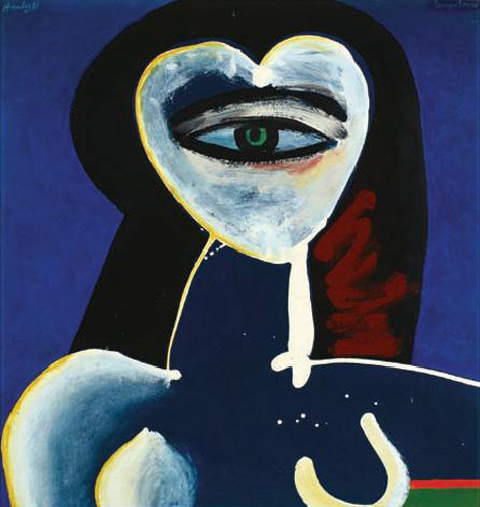

Pat Hanly

Lunar Lover I

They say that love is blind. If this is true, then it is a paradox, and equally true, that lovers see more clearly; innocently. The lover sees in the loved one, qualities only glimpsed by others. If lovers are blind in one eye, they are all-seeing with the other. They see more deeply, more roundly; grasping the beauty that unfurls when the heart says “yes.”

Hanly sees with the fecund clarity of the lover. His is the gaze of a lover of a woman and a child. He paints with the fleshy, wanton poetry of the satyr: eyes become full goblets of wine, and a love-heart swells as fleshy buttocks or juicy breasts. The very first book Hanly bought with wages from a hairdressing apprenticeship at the age of 14 was of Rembrandt's drawings; and more than 30 years later his paintings have the generous sensual power and romantic clarity of Rembrandt’s nude studies of Hendrickje Stoffels and of Picasso’s smitten and luscious oils of photographer Dora Maar. It seems ironic that back in 1948 Hanly’s mother quickly removed the Rembrandt book in the hope that her son would not be exposed to any nudes.

But the eye, steady and fixed in the centre of Hanly’s Lunar Lover I is also the innocent eye of wonder. It is the adoring one-eyed gaze of the new parent seeing the world through the infant’s pointing and looking.

Asked by Hamish Keith if social comment was intended in the mid-1960s series Girls Asleep, Hanly was emphatic: “Nothing to do with that at all. It was a highly romantic concept: of girls, in the first place, of sleep – the complete innocence that everybody, even the most vile person, takes on in sleep. You don't often see it in people because you're not always watching sleeping people – you’re usually asleep at the same time.”

For Hanly the best of the Girls Asleep were about this “innocence and delight.” Lunar Lover I delights in a similar innocence – that of the child seeing the world, fresh and new. While there are no children figured in the painting offered here, others in the Innocence series to which it belongs, do show a child: sitting between an adoring couple; or sitting apart and pointing at a bird in the sky or the moon. So it is, that the single eye in Lunar Lover I doubles as the child’s wondering “eye unclouded by experience” and as the parent’s adoring gaze.

Previously published in Important Paintings and Sculpture, 22 May 2008, Art+Object 21st Century Auction House, Auckland, pp28-29.