Rob Garrett

Curator

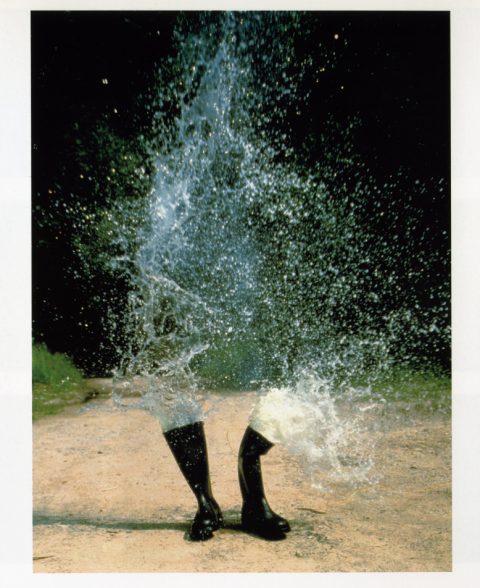

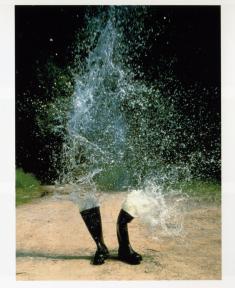

Exploding Water

Roman Signer in Auckland, 2008

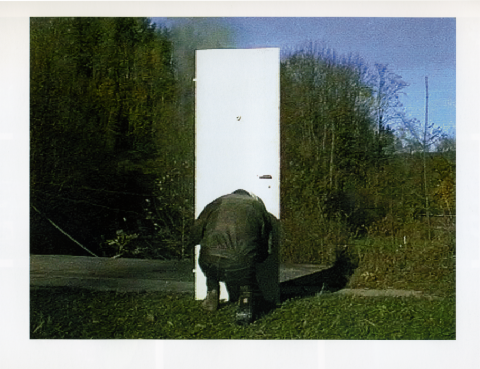

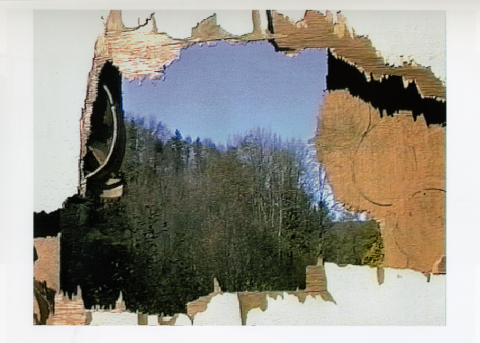

A pair of black gumboots stands in a country road. Suddenly water explodes from them. This surprising moment is captured in a colour photograph. Years later, a door stands by itself in the landscape. A man crouches low in front of the door, facing it. He presses a buzzer and an explosion tears a hole in the upper part of the door. The man stands and peers through the hole out into the scenery.

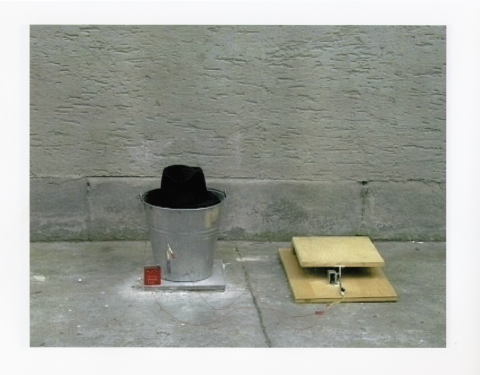

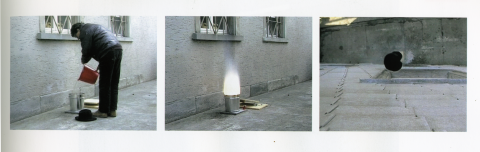

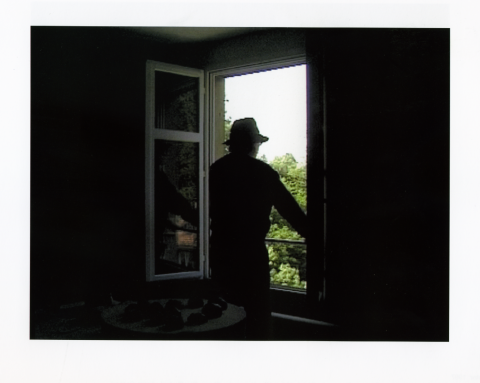

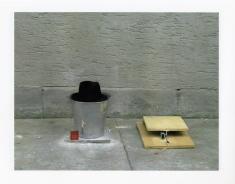

Three years later, the same man fills a bucket of water at the side of a house. He places a black hat over the bucket. Next to the bucket is a battery with cables leading to a wooden hatch. Moments later the man appears at an open window several storeys above. He secures a safety rope around his middle – though there is clearly no danger of falling. Taking careful aim, he drops a ball of plasticine out the window to hit the hatch below. There is an explosion in the bucket which propels the water and the hat skywards. The man attempts to catch the hat. He fails. He repeats his actions. He fails again, and again. We are shown this in slow-motion. Now we watch in real time and hear the sounds of the event. He catches the hat. He places the hat on his head and silently stands at the window to look at the scenery.

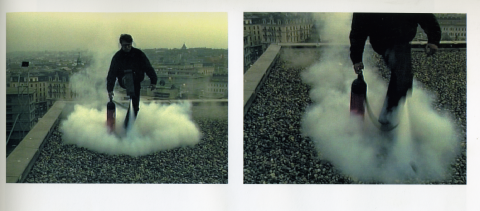

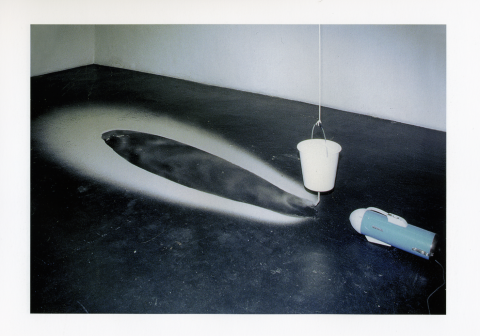

Roman Signer (born 1938), with a career spanning three decades, is one of Switzerland’s most important and influential contemporary artists. Having come to wider prominence through Sculpture Projects, Münster 1997 and the Swiss Pavilion in the 48th Venice Biennale, 1999, he is famous for his spectacular explosions; kayaks dropped from helicopters; and bicycles, tables, buckets and chairs propelled through the air.

In Auckland this past autumn, 16 video works from the past two decades were shown at St Paul Street Gallery, Artspace and two public windows. These exhibitions were an exploration of the artist’s interest in time as sculptural material, and were the first solo showings of Signer’s work in the Southern Hemisphere. In a new book (Sculpting in Time, Kerber Verlag) which accompanied the exhibitions, the authors and gallery directors Leonhard Emmerling and Brian Butler, develop a new interpretation by concentrating on the film works and by attempting to shed light on the temporal aspects of the artist’s work.

Roman Signer says “everything is very clear” in his pieces, “very transparent, easily understood.” This has not stopped commentators reading Signer’s apparently absurd and arbitrary endings as anti-climactic; as if something else could have happened. However, looking beyond what is right in front of you in this way is exactly what Signer’s works seek to undo. The Auckland exhibitions permitted a renewed attention to what Signer shows us directly, not what might be missing; and what he shows us is that time is material. As a sculptor, he treats it the same way he treats mass, force and velocity. What his brief works reveal in their typically 1-minute duration, are a youthful wonder and the playfulness of a sculptor shaping time, second by intensely observed second.

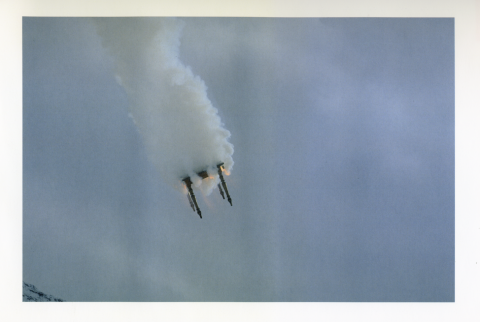

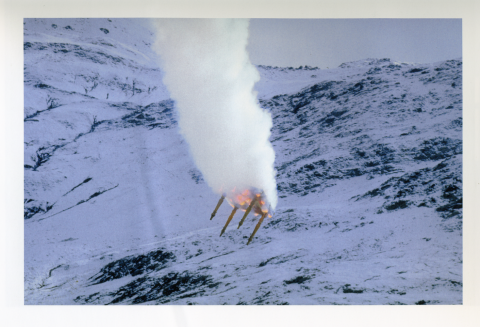

Youthful wonder does not experience time passing but is always in time. Signer’s events and actions are not composed of beginnings, middles and ends in the usual narrative drive towards a conclusion. Sure, they start and finish, but they seem to be entirely composed of middle, going nowhere. They are about the transformations that take place in the moment: an arm thrust upwards by the velocity of a rocket and falling back with gravity; a rocket-propelled table falls through the air creating a smoky drawing in space; water explodes out of a pair of black gumboots. Something is always irreversibly transformed – often it is our perception of things. The works induce the hypersensitivity to detail that our perception acquires (usually in a rush of adrenaline) in those moments when time appears to stand still.

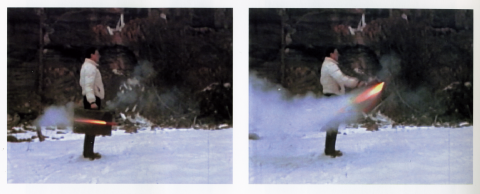

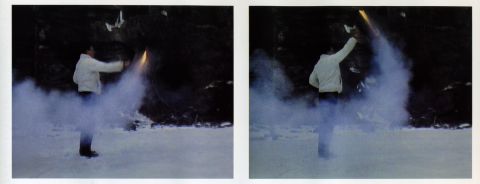

Think about standing with a rocket strapped at the sole of your boot. Think about firing this rocket in short bursts. Hiss-whoosh! Let your leg swing freely upwards with the force. Think about trying to turn this upwards swing into a step forward, a kind of goose-step. What does the rest of your body want to do? What does it need to do, to let you achieve both the free upward swing and the step forward? Try it. This action is impossible without letting your body discover a new sequence of movements; new shifts in weight; a new balance between stasis and momentum. Try this and you may re-focus your perception of your body; and you will shape time to accommodate a new way of feeling and seeing. You will need to stretch time to see and feel more clearly what normally happens without thought, in an instant: you take a step.

Footnote: Roman Signer’s words are extracted from an interview with Angelo Capasso, Esculturas e instalacións, Centro Galego de Arte Contemporánea, 2006, pp223-225.

This review of the pioneering Swiss artist Roman Signer's work by Rob Garrett was written on the occasion of the artist's first exhibition in the southern hemisphere of the artist's work, at St Paul St Gallery and Artspace, Auckland, 14 Mar – 19 Apr 2008. Previously published in Art World, Issue 3, June/July 2008, pp168-169.