Rob Garrett

Curator

Richard Killeen

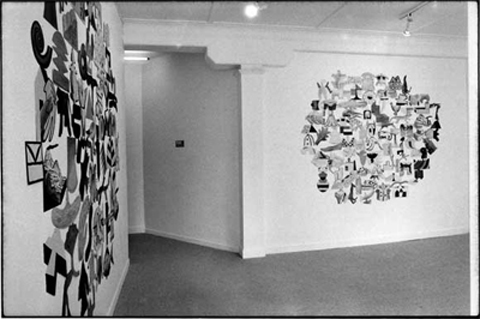

Monkey's Revenge, 1987

While Creationists say any search for evolutionary missing links has been fruitless, Killeen proffers a hyper-abundance of links – with Charles Darwin presiding in the centre. The 1987 cut-out Monkey’s Revenge is from one of the key transitional periods of the artist’s impressive career.

1986 and 1987 were turbo-charged years in Killeen’s practice with exhibitions of major new work in New York (Bertha Urdang Gallery), Sydney (Ray Hughes), Wellington (Peter McLeavey) and Auckland (Sue Crockford). They were years in which he was trying several new ways of linking, multiplying and juxtaposing a refreshed cornucopia of imagery. It was a period where drawn, photocopied and hand-coloured pictorial elements predominated over the pared back abstract and silhouette forms of the previous cut-outs

The variety of his approaches in these years demonstrated his confidence and maturity. Forms drawn and painted on tissue and glues to small irregular sheets of aluminium populated gallery walls in tight clusters of 80 and upwards. Framed works on paper combined half a dozen or more related symbols in loosely, but precisely composed vertical arrangements. Paintings on canvas re-emerged, but with a visual repertoire gained from the cut-outs. Polystyrene clouds the size of a person’s chest, covered in pastel and acrylic collages of Killeen’s signature lexicography also sprouted on the walls like conglomerates of the cut-outs – as if all the little aluminium sheets, like scattered mercury, had pooled together and left a selection of images floating on the surface of a single bulbous form.

But it was the aluminium-mounted cut-outs that were the source. You will notice that several shapes in the bottom row of Monkey’s Revenge pre-figure the new polystyrene-mounted conglomerates that emerged in 1987. Rather than figuring a single image they amass an intertwining and layered cluster of shapes and images. Monkey’s Revenge is a significant work where all these strands come together, bifurcate and quadruple in variety and freshness. If Darwin is the key to this puzzle, sitting as he does in the middle, it is perhaps to preside over Killeen’s primordial swamp from which much of the next decade’s work sprung.

As if mirroring the personal – the Killeens had a toddler in the family – the artist’s studio prolifically birthed forms and ideas and new sub-species. Monkey’s Revenge has symbols of origins, journeys, oddity, and status in abundance: rhinoceros, maze, a pair of angel wings, blacksmith’s anvil, fossil shell, a little square corral of sperm, Aztec and Egyptian hieroglyphs, bolts and machinery, and fragments of heraldry. Killeen populates his Revenge with everything from protoplasm to the markers of mid-century Modern civilisation, indicating a rich soup of cross-references and cross-breeding. But stopping as he does with an early skyscraper it was as if Killeen as social commentator saw the present and future as entirely in question – unable to be divined or excavated.

Richard Killeen, Monkey’s Revenge 1987, pencil, acrylic and collage on aluminium, 80-piece cut-out, dimensions variable.

Previously published in Important Paintings and Sculpture, 27 November 2008, Art+Object 21st Century Auction House, Auckland.