Riding with Alan Gibbs in his Jeep, we went down to the edge of the harbour to look at the Goldsworthy. We had to drive out along a shell bank with the water lapping at both sides. The end was blanketed by a vast flock of roosting oystercatchers waiting out the high tide. Shells crunched under the tires and the wind tugged at our jackets as Alan inched the vehicle towards the birds. In wave after wave they quietly, unhurried, lifted into the air, borne on the shore breeze with only the slightest movement of their wings. Hovering, they drifted out a little into the wind and back over our heads to settle again behind us. We stopped. The teeming birds formed a silent arc over our heads that echoed Goldsworthy’s stone arches marching through the shallows next to us. I caught a glimpse in this moment of how one could be tied to such a place. It is the sort of place that makes one pause; take time; take time out. Though it is the antithesis of many other things in life, it also has the power to tether one to life.

Seeing him here, traversing the rolling landscape of his 1000 acre New Zealand property, talking about one sculpture after another, is to feel Gibbs’ excitement for the place and the art. He is as enthusiastic as a boy in a toy store; and with good reason. When he bought the land now laconically known as The Farm, in 1991, he already had three decades of significant art collecting behind him. Commissioning art works was in the back of his mind “but not the major purpose” of searching for a rural retreat. Looking back, it is clear now that 1991 marked the beginning of a whole new art collecting adventure for Gibbs. He is a rare breed for several reasons. He has made a total commitment to open-brief commissioning of major site specific works from key artists. He is forming a collection of permanent private commissions of the scale that nowadays are more often temporary and the province of public institutions. And he has adopted an expanded role as collector. By rolling up his sleeves alongside the artists, he too faces the boundary-pushing challenges that come with an open brief: to play, puzzle and solve. Gibbs has become the artists’ accomplice and is often, as a consequence, the art producer.

Alan Gibbs and his then wife Jenny started collecting in the 1960s. By the early 90s when they parted company, they had amassed probably the best collection of works by key New Zealand artists including Gordon Walters, Colin McCahon, Milan Mrkusich, Stephen Banbury and Max Gimblett. After starting with an interest in abstract expressionism, Gibbs admits to “a fairly developed taste for abstract minimalist art.” This has informed the selection of artists for his rural New Zealand project just an hour’s drive north of Auckland.

The land has first place in Gibbs’ heart. It is a place where he can relax and play. The art collecting comes second to his project of re-shaping the landscape through an ongoing programme of softening gullies, re-contouring ridges, restoring wetlands by building lakes, and devising the best tree-planting approaches. Further, The Farm is his home for only three months of every year, for he is very involved in his London-based business. Gibbs is one of New Zealand’s most successful entrepreneurs. He has achievements in engineering, manufacturing, diplomacy, merchant banking and telecommunications; and is now active as founding chairman of Gibbs Technologies, the world leader in the development of High Speed Amphibian technology.

Nevertheless, his commissioning shows the hallmarks of an ambitious and motivated plan to create an internationally significant collection. After just seventeen years Gibbs’ collection includes major, and in many cases the largest works by Andy Goldsworthy, Anish Kapoor, Bill Culbert, Chris Booth, Daniel Buren, Eric Orr, George Rickey, Graham Bennett, Kenneth Snelson, Len Lye, Leon van den Eijkel, Marijke de Goey, Neil Dawson, Peter Nicholls, Peter Roche, Ralph Hotere, Richard Serra, Richard Thompson, Russell Moses, Sol LeWitt and Tony Oursler. Collected at a rate of about one a year (though many take 3-5 years to develop) all bar two of the sculptures are unique and site specific. While The Farm cannot yet rival the depth of Storm King, Gibbs’ artists and works compare well. In some cases they surpass. For instance the Serra, Buren and large Rickey are more significant works than their New York counterparts.

Gibbs’ passion, will and audacity are key. As Richard Serra said: “The first thing he said to me was ‘I’ve just been to Storm King [where Serra has the “fairly consequential” Schunnemunk Fork 1990-91] and I want a more significant piece than that. I don’t want any wimpy piece in the landscape.’ Alan was throwing down the gauntlet and he said ‘If you’re going to do something here I want your best effort.’” Gibbs adds that “the challenge for the artists is the scale of the landscape; it scares them initially” and demands something more from them.

Each project requires several site visits before a concept is agreed upon and developed. The artists live on The Farm with Gibbs and his family. Daughter Amanda and architect and son-in-law Noel Lane run the place now that Gibbs is in London for most of each year. Gibbs says the family has evolved their taste on the land and the collection together. Noel Lane especially had a lot to do with dealing with Anish Kapoor and his work at all levels; and with the engineers in relation to the detail of the design and construction of most of the works. With the artists staying for a week or ten days at a time, being away from most of their usual routines and distractions seems to be a boon. Gibbs recalls during Serra’s visits the two would enjoy arguing politics into the small hours. Kapoor brought his family with him for his three visits. During Goldsworthy’s four visits he would work all morning, making his ephemeral temporary works. The visits also involved building full-scale mock-ups of various concepts for a permanent work, before artist and collector settled on Arches (2005), an elegant series of Roman arches made from Scottish quarry stone. The work loops across the harbour shallows and forms perfect shimmering circles when reflected in the wet sand of low tide.

Perceptions of the works shift with the changeable light that slides and folds across the rolling landscape; and with the varied perspectives afforded by walking or driving across the land. Gibbs’ care with the collection means that the landscape and the sculptures act in a graceful and dramatic counterpoint to each other.

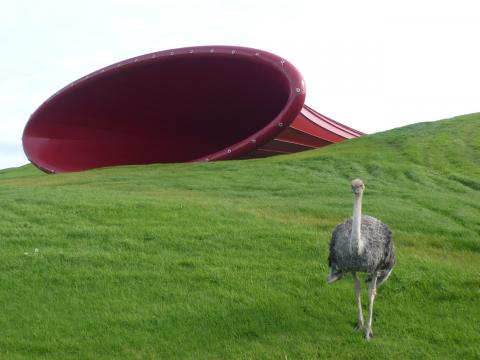

Anish Kapoor’s Untitled (as yet) 2009 is related to earlier temporary installations at the BALTIC and the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall. But it is an intensely more sensual experience because it is conceived for a wild and unconfined landscape. The previous works, Tarantanrara 1999 and Marsyas 2002, were made to fill the box-like voids of exhibition halls. On The Farm there is no prescribed space to work within. Rather there is an undulating plane, far horizons and a wide sky. In response, Kapoor has nestled the work in a cleft cut into a high ridgeline. With views of the harbour to the west and mountains to the east it is as if he wanted to channel the forces of water, air and rock; and to link the width of the harbour with the height of the hills. The site elevates Kapoor’s work into view, but also makes it impossible to be seen entirely from any one position (other than the air). Even standing on the ridgeline close above it, the sculpture can’t be taken in without turning one’s head from side to side. Seen from a distance, the landscape gives it a nudge, playing tricks on one’s ability to judge size and proportion. But standing close to the 8-storey high work, it’s gigantic, mesmerising character kicks in. Composed of a vast PVC membrane stretched between the two giant steel ellipses, it has a fleshy quality which Kapoor describes as being “rather like a flayed skin.” During one of the site’s frequent westerly winds it takes on a life beyond what Kapoor could ever achieve indoors. One can sense the wind, as one feels the breathing of someone lying nearby. Entering from the west, it doubles in force and its materiality is amplified, as it passes through the narrow waist and out the wide horizontal mouth of the leeward end. The sculpture breathes: expanding and contracting with each gust. Here Kapoor has realised something transcendent within a large sculptural object. It is architectural in scale yet mysteriously visceral and immediate in character. It is thoroughly exhilarating.

Richard Serra’s Te Tuhirangi Contour oscillates between two characters too, no matter how often I see it. Viewed from any of the ground above it, the 257 metre steel wall has a delicate quality like a dark ribbon curling, almost floating across the evergreen pastures. The deception is beguiling until one walks nearby and underneath the 6 metre high sculpture. Here one is confounded by an altogether different experience. From the downhill side Te Tuhirangi Contour has all the mass of a giant dam filled with water. Each of the 56 steel plates leans out by 11 degrees from the vertical, so the materiality of mass and form impose themselves dramatically as something more felt than seen. Serra said that he wanted to create a work that in some way “collects the volume of the land;” and he has.

Serra and Gibbs agree the work exceeds their anticipation. Gibbs says “I’m absolutely thrilled with it. I think it’s magic!” Yet the project nearly foundered; not once, but twice in the 5 years it took to achieve. First there was the impasse. After several site visits and various concepts, the artist and collector settled on one idea. They commenced building a full-scale mock-up in timber and builders’ paper in situ. At first they thought that if they were going to work in steel they would be limited to 16 feet high. This was mocked up but did not have enough drama; nor did 18 feet. It was only at 20 feet high that the scale worked. “But Richard didn’t know of any steel mill in the world that could form these steel plates 20 feet high;” and Gibbs suggested he make the work in concrete (as the artist had used concrete before). However Serra recalled “I wanted to build it in steel or not build it at all.” Gibbs and Serra were opposed. Later “Serra found a steelworks in Germany that could do it and he twisted my arm very hard and I decided, alright, it was so exciting that we would do it.”

Then, there was a near disaster. “Everything here is the biggest art work the artist has ever done.” Therefore Gibbs shares the challenges inherent in stretching artists beyond their experience: “We end up having to make the works.” Once made, Serra’s 56 computer designed plates, each weighing 11 tons, were handed over to Gibbs in Germany for shipping to the site and installing. “The work was designed to be stacked in the ship only ten plates high. In fact the captain of the ship ignored the instructions and stacked the plates 22 high at which point they fell over, nearly sunk the ship and damaged some of the plates. Every plate had to be individually set up again and re-measured; and most of the plates needed some re-working. Now that took a whole year.”

There is a discoloured band, about half a metre deep, all along the base of Serra’s sculpture. This is where sheep have rubbed themselves against the warm steel and left a distinctive patina. It is a high tide mark of the work’s sensuality; its attractiveness. The smudge grounds the sculpture in something homely. It is the earthy antithesis of abstract minimalism. Yet it is also perfectly in tune with this place and with the man. For Gibbs’ project as a whole encompasses a compelling collusion between the specifics of place, namely attachment and sensuality; and the abstractions and ambitions of an international art world, namely mobility and ideas. “Your best effort” always involves imagining somewhere other than where you are, while paradoxically being acutely aware of where you are.

Originally published in:

-

Art World AUS/NZ Edition Issue 9, June-July 2009, pp54-65 as "The Farm: Alan Gibbs – businessman, collector and artists’ accomplice. Rob Garrett takes an exclusive tour of Gibbs’ Kaipara (New Zealand) property and interviews the collector for Art World"; and

-

Art World UK/Int’l Edition Issue 12, August-September 2009, pp124-129

Re-published in:

-

The Australian WISH Magazine, Art & Design Issue, 6 November 2009, pp20-24 as “Landmark Decisions”

See more of Rob Garrett's writing on the Gibbs Farm collection

here...