Rob Garrett

Curator

Shane Cotton

Wake, 1995

Wake is a major Shane Cotton work. Effectively one of the anchor stones from the first mature period of his oeuvre which has been dubbed his ‘history’ period (1994-98). In 2003, for the landmark survey of Cotton’s early career, Wellington’ City Gallery marked the singularity and grandeur of Wake by hanging it on the wall of their foyer. Facing the entrance it was a gathering call to all visitors: Ā, tōia mai, Te waka! Ki te urunga, Te waka! Ki te Moenga, Te waka! Ki te takoto runga i takoto ai, te waka! *

Wake is a painting that says “Game on!”

Cotton (b. 1964) began exhibiting in 1987, had his first solo show in 1990, was shown at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery as early as 1995 and the Dunedin Public Art Gallery in 2000; and then City Gallery Wellington presented their ten-year touring survey of his works in 2003. By then, and seen through the lens of the City Gallery show, it was clear Cotton was embarked on a complex, nuanced and deepening trajectory as a painter. “Wake” occurs at the moment when his paintings became more detailed, amassing new layers of complexity.

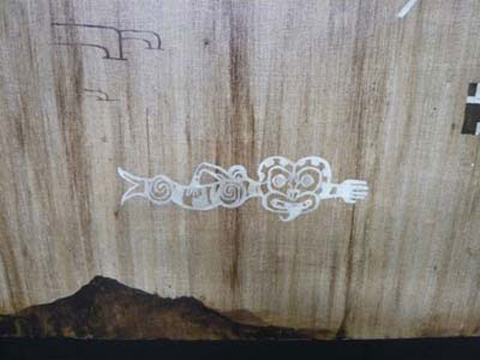

The canoe in Wake is like a giant pixellated world of its own: a collection of dark brown oblong and square panels floating on a sepia, faux wood panelling wash. The waka is an admixture of digital LED numbers, the spindly writing of Hongi Hika, lashing patterns, pasifika frangipani motifs, dots, dashes, lightening flashes, tukutuku lozenges, inverted landscape paintings, and basketballs. It reminds me of a giant sliding tile puzzle as if Cotton tantalises us with the possibility that each piece might be re-arranged. Though I doubt the parts would coalesce into a more logical whole, the invitation to slide things around, to play with the puzzle and look for patterns is probably quite deliberate. Calling this painting of a waka Wake in the first place is an open invitation to the game of word associations: wake, lament, waka, haka, wake up! The basketballs also invite gaming with this painting. Cotton’s dispersal of the small orange balls across the canvas calls to my mind the “ping” and “boing” of practice sessions in an almost empty gym, or an outdoor asphalt court in the misty, sweaty quiet of evening. In its power to evoke an associative mixture of staccato and resonance the painting is a taut surface for our imaginations, memories, and bewilderment to bounce into and off.

The mid-90s is when Cotton was developing stories from the North as if to recreate his tūrangawaewae, his ancestral home, outside the region and in the idiom of contemporary art. Cotton is of Ngāpuhi descent on his father’s side and of Scottish and English descent on his mother’s. His father’s family come from Kawakawa, Northland where Cotton spent many childhood holidays with his extended family. Using the visual language of the Ringatū figurative painting tradition; Ngāpuhi motifs that had been expunged by early Christian missionaries (such as the sinuous eel form that populates the sepia ground in Wake); popular culture; and references to his art world contemporaries (such as Jeff Koons’ floating basketballs from 1985), Cotton re-tells Ngāpuhi history.

We can see his Northland landscape repeatedly rendered in Wake, most especially the sacred mountain Maungaturoto, where it is mostly deployed to form the hull profile of the waka. This meeting of the sharp underside of the waka (its keel) with the pointed mountain is not an accidental or purely visual pun. The ancestral waka of Ngāpuhi, Mataatua – you will see the name inscribed across the top of the painting – made first landfall in the Bay of Plenty, and then found its final resting place in Cotton’s ancestral homeland, Northland at Tākou Bay. His waka and his land are joined. His waka rests on his mountain. His mountain greets his waka. Ā, tōia mai, Te waka!

* Tōia mai te waka is a haka of greeting and welcome; and can be used to allude to the histories, ancestry, ideas and purposes that people bring with them to the gathering at which it is performed. The haka can be translated as: Drag hither, The canoe! To the entry, The canoe! To the berth, The canoe! To the resting place to lie. The canoe!

Shane Cotton, Wake, 1995, oil on canvas, 1900 x 2750mm

Previously published in Important Paintings and Sculpture including the Odyssey Group Collection, 30 July 2009, Art+Object 21st Century Auction House, Auckland.