SCAPE 2010 Preview

Awakening a pedestrian citizenry

SCAPE 2010 Public Art Walkway raises questions about living and walking in the inner city and the ways festivals of temporary public art engage with the city as a given situation. Framing a biennial as a walk of art is logical in a city such as Christchurch, which is small, flat and easy to traverse by foot. The relationship between the pedestrian and the inner city as a place where people linger is also connected to notions for improving inner cities, and making them more attractive to people; and in the case of Christchurch there is also a link to a new focus on residential intensification. As Danish city planner Jan Gehl, one of the champions of transforming cities for the benefit of pedestrians, has said, “a good city is like a good party; people stay longer than really necessary, because they are enjoying themselves.”

The role of public art as a key component in the reshaping of urban environments is well known. However, the public art thought of in this context is usually of the permanent and semi-permanent variety. Temporary public art projects and programmes often occupy a different and interventionist space in people’s imagination. Does the differentiation hold? What are the relations of temporary public art projects and programmes in streets, alleyways, vacant lots, squares and other non-gallery public places to the drivers and processes of city planning? Further, what is the nature of the dialectic between place making where public art is a key component in the planned re-shaping of urban environments; and critical interventions, where public art draws from post-conceptual contemporary art practices with their decades old roots in the activation of various political agendas and the participation of so-called marginalised groups?

Broadly speaking permanent and semi-permanent public art projects being developed by cities currently are part of city improvement, redevelopment and regeneration programmes. The best of these are generated through thoroughly integrated planning processes and site-specific requirements, while many others still arise as a sort of end-point dressing of buildings, foyers and plazas. These projects are linked to a centuries-long tradition in which the city is conceived as a grand curatorial project, where public space and aesthetics are designed for the instruction, pleasure or inspiration of the populace, whether in service of notions of institutional power, statehood, design excellence, culture and heritage preservation, or community expression.

It seems easy to suggest, or assume, in contrast, that temporary art projects and programmes in the public domain do, or can dance to a different tune; perhaps to a more disruptive, critical and questioning tune. But is this really the case? On the one hand, yes, it seems possible that there can be a critically disruptive power in the temporary interventions; but on the other hand it is not necessarily so.

In the first instance temporary public art projects largely arose in 20th century cities as artist-initiated events, happenings, performances and installations, rather than as city commissions; and either did not need or did not seek planning permission. That many of these brought the experimental forms and modes of presentation of conceptual art into the public domain that would otherwise only seen by a very small coterie of artists, curators and patrons made them interventionist and disruptively challenging on many levels. Artists saw the city, and its public places, as a new and non-institutional situation for contemporary expression and social disruption. As such they engaged in the public realm as cultural citizens, contesting its norms by their actions and very presence. Many post-conceptual artists are still engaged in a similar dynamic through their self-organised art making and presenting in public places. However, commissions of temporary, ephemeral and performative public art projects by cities, corporations and biennials in recent decades raise a new set of questions. What are the drivers and motivations of the commissioners? Is the rhetoric of intervention in these cases any longer pertinent? What is the nature of disruption or critique if the projects are in fact integrated within a programme that is not only sanctioned, but invited, by the various institutional alliances (government, corporate, cultural) which lead the meta-project of curating the city; and where curating includes city planned up-grades and regeneration, district plans, the regulatory environment, private-public development projects, public art planning (including biennials), and public events planning?

Before addressing these questions, it is worth bearing in mind that among the myriad reasons people are attracted to cities, whether as residents in the inner city or its suburbs, is because cities are not close-knit or homogeneous communities. While many people seek attachment to community, we also seek the stimulation of the unknown, the unpredictable and the anonymous. Cities give us these things. Cities offer discordant, personally disruptive, troublesome and paradoxically exciting experiences of dealing with strangers; as well as the liberating experience of anonymity. These are among the reasons people seek out contact with and immersion within larger populations than those offered by the family, village and local neighbourhood. In fact both are needed: the dislocations and chance encounters of the city and the familiarity and closeness of the community.

Returning to our question about what motivates public sector commissioners such as city planners and public art curators who are interested in temporary “interventionist” public art projects, it will be evident from comments above that at least one attraction of these projects is that they are capable of generating unexpectedness in the planned creation of an attractive city. City planners, who understand the diversity of post-conceptual art practices, are highly likely to, do fact, embrace various performative, ephemeral and temporary public art projects for the very fact that they create surprises for the city’s populace. Such projects will be commissioned because it is expected that they will delight some members of the public and puzzle or even annoy others. One elected official recently expressed their hope to me that their city’s revamped public art programme would include the most innovative temporary projects in order to, over time, “educate” the general populace in the range of artistic possibilities that could be achieved by a public art programme in a “world class” city and thereby broaden popular support for more “challenging” permanent works in the future.

Finding the best approaches in any city’s situation relies on a profound understanding of the local, but it can also be opportunistic. I am reminded of a moment during the opening of Moscow’s 2nd Biennale of Contemporary Art in 2007, which as a winter biennale staged in minus 10°C to minus 20°C is necessarily an indoors event. The Biennale’s philosophical conference was held in the midst of the high chic glamour of the TsUM department store close to Red Square. While the conference took place in an upper floor that had been stripped out for re-development, the proceedings had been piped in their entirety, in Russian, through the department store’s PA system. Bulgarian curator Iara Boubnova commented: “Something we have learned in this country is that you need to take every opportunity to educate the people!”

It remains pertinent to ask again, what disruption or critique is possible if the projects are in fact integrated within a programme that is not only sanctioned, but invited, by the various institutional alliances which lead the meta-project of curating the city.

Is the notion of intervention in the case of temporary public art projects and programmes any longer pertinent? It may be, for even these commissioning situations create opportunities for the surplus production of ideas and sensations that derive from artists’ autonomy, and which are quite likely to exceed the scope of the commissioning programme and any instrumentalist drivers to fully anticipate reframe, or entirely accommodate. For the system of deploying temporary public art projects as a mechanism for producing the lively city relies on artists’ autonomy, even within the strictures of the brief, otherwise there is no creativity generated and contributed to the situation. The arrangement also relies on a degree of autonomy in the populace, manifested in the possibility of diverse receptions of the work. Both the autonomy of the artist and of the populace are required otherwise, the phenomenon of unexpectedness is not produced in the exchange; and by extension if unexpectedness is not produced in the exchange it no longer circulates within the production of the city as a situation that includes liveliness, surprise and mystery.

In the desire to recognise and commission an interventionist art in the public sphere I am inclined to believe that it is the form and structure of the art that matters, not the content. Here I agree with Paolo Virno when he asserts that “art that relates to social resistance is beside the point, or rather art expressing views on social resistance is not relevant.” What is relevant is the way that the form of the art suggests new structures and thereby suggests the form of a new public sphere. In this regard, the simple instrumentalist programme of the city councillor to encourage more temporary public art in order to engender an expanded understanding of what is possible touches on a truth. In so much as temporary public art projects confront the populace with new, and likely bewildering, thought-provoking, conversation-stimulating forms and structures, they have the potential to infer that our understanding of existing forms and structures are inadequate, and to stimulate greater openness to and enquiry after new ways. This is the optimistic possibility: that alternative futures will be imagined.

In curating the 10th International Istanbul Biennial in 2007, Hou Hanru sought to emulate the city’s sprawling, fragmented and dynamic energy, while referring to its current situation in a globalising world and an expanding Europe. Turkey, then and now, faces considerable challenges as it seeks acceptance by the European Union: incompetence and corruption, inequities between rich and poor, and though the free flow of information has improved, there remain challenges to free speech in the rise of a reactionary secular nationalism. In this context, public art interventions linked to democratising propositions and calls for a civil society were timely. An exemplar was the biennial’s Nightcomers programme, which through its structure and form sought to open new public spheres in the informal and distributed public places across the city. Hou Hanru looked back to China’s Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 1970s, when the “lower class” was encouraged to post their critiques of the elite in the form of Dazibao (a journal or poster with large letters). Hou noted that at this time “street corners became public forums. In spite of totalitarian propaganda, this approach showed a form of radical democracy.” In seeking a similar, but contemporary, equivalent of this for Istanbul he commissioned the Dutch artist couple Bik Van der Pol (Liesbeth Bik and Jos van der Pol) who had been resident in Istanbul for the preceding five months to research potential sites throughout the sprawling semi-regulated city. He also invited five local curators to select over 150 short video works for these public locations from the multitude of videos submitted by artists and members of the public after an open call. The videos were projected onto 59 vacant sites, walls and street corners across the city. Hou claimed that for the first time in the history of the biennial “a real open participation of the public has been made possible so that thousands of people living in areas without access to ‘high culture’ can have direct contact with contemporary art”. Venues included the top of the old Galata bridge, which had suffered a fire and had its middle section removed; a densely populated public square with ice cream stall, mosque, fountain and cafes; a vacant wall at a crossroads; and a bus station on the periphery of the city, with public toilets and a public square where “lots of people pass, wait, hang around, go to the toilet and wait a bit more”.

The form and structure of the project made it almost impossible for the globe-trotting members of the biennial’s audience to experience directly. Dispersed across so many sites in a vast and bewildering city, for biennial guests on tight 3- or 4-day schedules, Nightcomers was largely out of reach. This is important for it points to a central question in all of these programmes: who are the addressees? In the case of Nightcomers, the primary addressees were the local residents, workers and itinerants in each of the dispersed locations. Secondly, how were they addressed? The structure and form of this project was an intervention in, and a constitution of, a public sphere. Its distributed locations; the fact it would be experienced in fragmentary form (or the impossibility of experiencing the whole); the freely submitted content selected by locals evoking notions of free speech; and the presentation on the streets; all pointed to an aspiration to not only address, but to constitute, a pedestrian citizenry. As people paused, watched, listened and engaged with both the content of the videos and their very appearance in public there was the possibility they would constitute themselves as a public; and so, if one of the functions of public art is to induce pedestrians to stop and look, to linger, then the critical question becomes, with what result?

It is here we can return to one of my opening remarks that Christchurch’s small size, compact inner city and vision for residential intensification draws our attention to the relationship between the pedestrian and the inner city as a series of places where people linger. City planning proponents of attractive cities observe there is a direct correlation between the pedestrian-friendly inner city and the length of time people stay in the city in excess of their original purposes for their own spontaneous enjoyment. Reducing the dominance of private vehicles in the inner city, making the city easy to navigate for pedestrians and improving public transport and cycling are all-important urban planning strategies to that end. Equally important are considerations of spatial scale and variety at street level. People’s walking gait slows down when there are things to look at, touch, smell, hear, investigate and engage with. When street level facades of buildings offer unbroken masses they are perceived as closed and unwelcoming and pedestrians speed past. Conversely, when the street-facing ground floors of buildings are broken into human scale proportions and offer interesting and varied experiences, people will slow down and take their time. Public art, whether permanent or temporary, has become essential to city planners wishing to increase the variety and stimulation of experiences on offer to pedestrians in the inner city.

When cities are easier, safer and more amenable for people it is also highly likely that their businesses thrive, employment increases, and more residents are attracted to the inner city. Equally, the intensification of cities and the associated increase in pedestrian uses of the city mean that people mingle more, bringing them face to face with strangers and otherness, and heightening experiences of difference. This situation creates the conditions for greater social acceptance and potentially for new forms of collectivism and public structure.

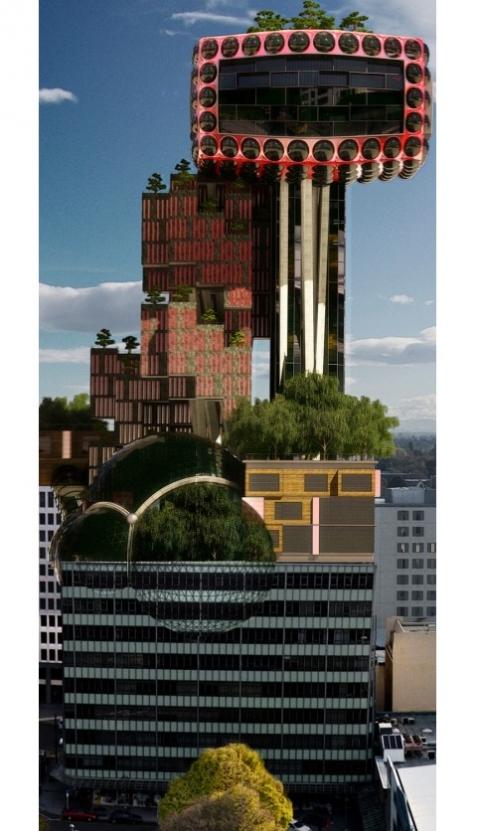

SCAPE 2010 Public Art Walkway by its very structure as a programme of novel and temporary public art projects plays into the aspirations of those who would make a more attractive and engaging city for residents, workers and visitors alike. Yet its forms and structures may, at the same time, cut across society’s predominant notions of how things should be organised, to propose new structures and forms. I find it promising and intriguing that of the seven new large-scale temporary public artworks that the Curatorial Group of Blair French, Julia Morison and William Field have commissioned, four engage with notions of the inner city as home, and therefore seem to consciously address the situation of the city generated for and by its residents. The projects by Héctor Zamora, Ash Keating, Joanna Langford and Richard Maloy each question accepted notions of development, building, social organisation and domestic architecture.

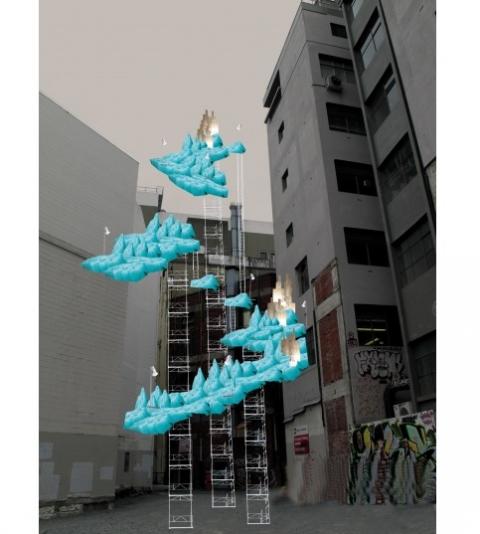

Joanna Langford’s installation is emblematic of the way such work can suggest new forms. Describing herself as an anti-engineer and inspired by the phenomena of spontaneous architecture around the world, such as the cave dwellings of Cappadocia in Turkey, Langford has created an aerial futuristic city that hovers above an empty lot. Built on raised platforms supported by scaffolding; and made from plastic milk bottles which are illuminated from within by LED lights; the structure apparently floats on clouds of plastic wrap. Its form and structure is intended to create an experience “that is so physically different” from where we have just been “that it feels like anything could happen and it heightens your imagination”.

In presenting an alternative architecture and inferred forms of social organisation where the accepted commitment to current rules and models fail to cohere, Langford hopes viewers will re-engage with their intuitive desires alternative modes, structures and principles of living. This is a fundamentally public form of imagination in that it transforms the individual from private person to public citizen in two ways. First, this imagining requires that the individual think of themselves as a member of the “we”, as in relation to others, and not simply the collective of the family or the group, but that of a populace, the collective of strangers with whom they will have to share the task of re-organising things. Secondly, it relies on the individual visualising or sensing themselves engaged in the actions required to re-organise things; as an active agent of change. To the extent that any public art projects stimulate similar transformations of the private individual to the public citizen through the spaces of imagination that they open up, they can claim to be interventions in the public sphere.

Previously published in Contemporary Visual Art & Culture Broadsheet 39.3 2010, as “Awakening a pedestrian citizenry,” pp172-175

Christchurch Earthquakes in late 2010 and then finally and fatally, the February 2011 quake, forced the radical postponement and re-thinking of the 6th SCAPE (planned for 4 March-17 April 2011). Read more here and here…

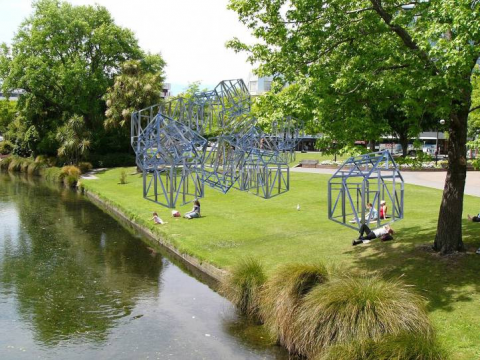

Finally, after the disruption of the tragic earthquakes in Christchurch, Joanna Langford's public art project "The High Country" was realised:

"The High Country" by Joanna Langford is an aerial utopian city installation that appears to be floating above its urban surroundings in central Christchurch.

"The High Country" was commissioned for the 6th SCAPE Christchurch Biennial of Art in Public Space in October 2010. Its construction was repeatedly foiled by the Christchurch earthquakes, however after much tenacity and perseverance it's installation was celebrated on a newly vacant site on Cranmer Square on 11th November 2012.

SCAPE Public Art installs large-scale, free-to-view contemporary public art in Christchurch City.