Peter Robinson

In This Lost and Forsaken Land

“In This Lost and Forsaken Land” comes from a period where Peter Robinson was provocatively questioning the effectiveness and legitimacy of using Maori motifs in personal, organisational and national identity gambits.

In the past decade the sovereignty debate has focused on seabed and foreshore ownership. In the nineties it was the appropriation of Maori graphic motifs and language by government departments, corporations and even artists to confer some sort of bicultural legitimacy that came under critical fire by Maori and cultural commentators alike. Given the fact that it was visual real estate that was contested, artists, Robinson included, were among the activists. Robinson’s art entered this fray with sometimes playful and at other times shockingly provocative signs such as swastikas, fists, shonky spirals; and slogans like “DIE PAKEHA,” “DIE MAORI,” “WHITES HAVE RIGHTS TOO” and “BOY, AM I SCARED EH!”

Painting in the bold contrasts of black and white, his works graphically illustrated the polar opposites of the appropriation debate. The fact that his paintings were more often line drawings and writing, they made more than a passing acknowledgement of the methods of two philosopher-teachers of the twentieth century art world: Colin McCahon and Joseph Beuys; the former, with his painted white poetry and prophecies floating on black; and the latter with his chalk board notations and diagrams spelling out a utopian social sculpture.

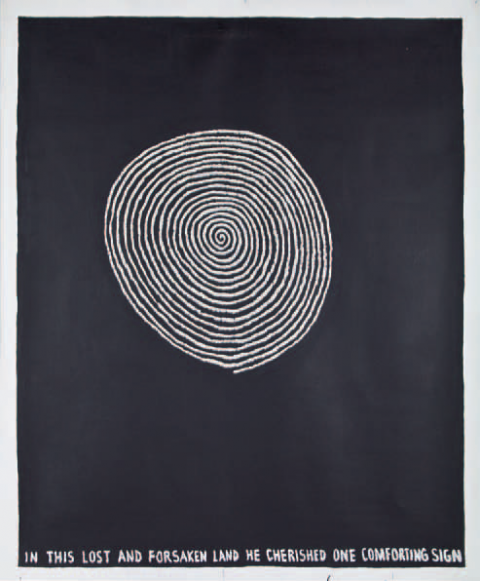

Robinson’s “In This Lost and Forsaken Land” is one of a series of works from this decade in which the artist draws a white spiral on a black ground. The spiral is as densely wound as a clock. It seems immediately reminiscent of the mesmerizing black and white concentric circles found in joke glasses and amateur hypnosis equipment sets advertised in boy’s magazines. Of course the spiral is also a tightly coiled koru. Why has the form adopted this tight, highly strung character in Robinson’s hand? Because the koru itself had become so argued and fought over; and the full inscription at the foot of the painting makes the irony clear, for this koru was far from a “comforting sign.” This and the other art works from the same period which use such title-slogans as “BOY, AM I SCARED EH!”, come at a time when McCahon’s use of Maori motifs was being lauded; while Gordon Walters’ koru paintings were ironically under harsher scrutiny; and while Te Papa was attacked for supposedly spending $300,000 on its new “Our Place” thumbprint logo. It is this logo, in which nature (genetic patterning) and culture (koru swirls) are collapsed into one form, that seemed to epitomise the problematic way an image might be used to try unify a national identity that even to this day resists coalescing into “One People.”

Robinson’s interest in the impossibility of signs being able to simplify, unify, reduce, or “comfort” complex and contradictory identities starts at a very personal level with the percentage works where he commented on identity notions based on racial blood. Then during the nineties he encompasses wider ideas of signs that languish under the task of representing national identity. This shift may partly stem from his accumulating experiences as some sort of cultural ambassador overseas. His first invitation was as a member of Priscilla Pitts’ New Zealand team at ARX 3 in Perth in 1992, and then he had more than two dozen exhibitions over the decade in France, Germany, The Netherlands, Belgium, Australia, South Africa and Brazil, perhaps culminating in the black and white binary code works of the next decade which made an early appearance when he “represented” New Zealand, along with Jacqueline Fraser, at the 2001 Venice Biennale of Contemporary Art. It was perhaps the personal way these overseas appearances as an emerging New Zealand artist, amplified by his received status as a young contemporary Maori artist, combined with the often passionate debates in New Zealand about cultural identity and appropriation politics throughout the nineties, that grounded Robinson’s critique and gave this and other works from the period their power.

Previously published in Important Paintings & Contemporary Art, 12 April 2011, Art+Object the 21st Century Auction House, Auckland, pp62-63.