Shane Cotton

Spirits Bay, 2002-2004

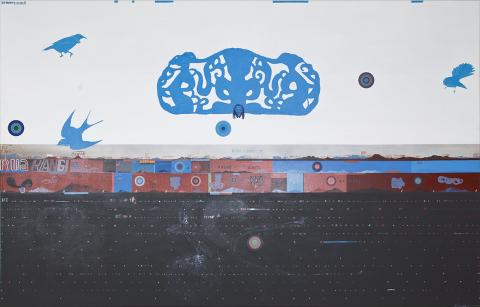

“Spirits Bay” by Shane Cotton (b. 1964) looks out to sea. Given there is no correct way to look at a Cotton from this period, no one path for connecting its distributed parts, I find myself starting with its wide flat horizon, its division into a pale top and a dark bottom; and within each half, further divisions; especially the division of the upper half into two skies (“RUA RANGI”) or equally into a sea and a sky both spread out, vast and pale above stacked coastal profiles and an inky depth below. These pale skies are the wide, white skies of a coastal summer: hot, hazy, bright; at one and the same time palpable and infinite.

Spirits Bay (Kapowairua) is located at the northern tip of the North Island to the east of Cape Reinga, and along its 12 kilometre length it faces north across the wide expanse of sea and sky stretching from Aotearoa to Hawaiki. The bay’s name comes from a Muriwhenua ancestor Tohe’s parting words as he prepared to travel to the Kaipara when he was very old, to visit his only daughter, Raninikura. Asked not to go by his family, who feared he would not survive the journey, he replied:

Whakarua i te hau, e taea te karo

Whakarua i taku tamahine, e kore e taea te karo

Taea Hokianga, a hea, a hea

Ko ta koutou mahi e kapo ake ai, ko taku wairua

I can shelter from the wind

But I cannot shelter from the longing for my daughter

I shall venture as far as Hokianga, and beyond

Your task (should I die), shall be to grasp (kapo) my spirit (wairua)

Cotton’s epic painting is a beautiful elaboration of a shift which took place in his paintings around 1997 in which he began to include imagery explicitly drawn from Ngapuhi. Among the references to specific landforms and places of the North, Cotton also includes a weaving together of both Maori and Christian iconography. Interested in what he has termed ‘bispirituality’ the paintings began to both comment on, and counteract the missionary legacy which had stripped Ngapuhi’s marae and meeting houses of their carvings, kowhaiwhai paintings and woven tukutuku panels.

The luminous coiled snake resting in the dark lower half of “Spirits Bay” for instance, references the early northern prophet Papahurihia, who set up a new religion in the name of the Biblical serpent which he didn’t hold to be unequivocally evil, perhaps based on ambiguous early translations of the Bible. Equally, the bright blue silhouette of a carved door lintel (pare), surrounded by birds, messengers from the spirit world, speaks of Maori and Christian notions of faith, resurrection and the afterlife. Pare usually feature a central female figure underneath whose spread legs and exposed vagina people must pass when entering the meeting house from the marae; thus, passing between her legs to travel from this world to the belly of the ancestors, or from this world to the next. In Cotton’s painting, the woman’s genitals are covered by the head of Christ (there is an image of a Maori Jesus at his home marae, Ngawha) marking both the memory of missionaries stripping carvings of their male and female genitals, and perhaps indicating the Biblical reference to Christ as “the Way”. Yet the presence of the Piwakawaka (fantail), which tittered at the sight of Maui’s legs sticking out from Papatuanuku’s thighs, is a reminder of the demigod’s failed attempt to wrest eternal life from the spirit world by crossing this same vaginal threshold, and lands us back on the shore, looking, perhaps longingly, out to sea.

Shane Cotton, Spirits Bay 2002-04, acrylic on canvas, 1900 x 3000mm

Previously published in The David and Angela Wright Collection of Modern and Contemporary New Zealand Art, 30 June 2011, Art+Object the 21st Century Auction House, Auckland, pp44-45.