Judge: Estuary Artworks 2013

Uxbridge, Creative Arts Centre, NZ

The award

Estuary Artworks (15 March – 26 April 2013) is an annual award exhibition run by Uxbridge and is in its 7th year. The competition is open to all New Zealand permanent citizens and residents over the age of 16. Entrants are encouraged to creatively respond to the Tamaki Estuary’s role in the Auckland landscape and to highlight the need for the Estuary’s protection and preservation. All entries must reflect and respond to this theme in a contemporary, innovative and intelligent way.

In 2013 the Judge awarded the Supreme Award to Belinda Griffiths; and Runner Up awards to Bernie Harfleet and Alby Yap.

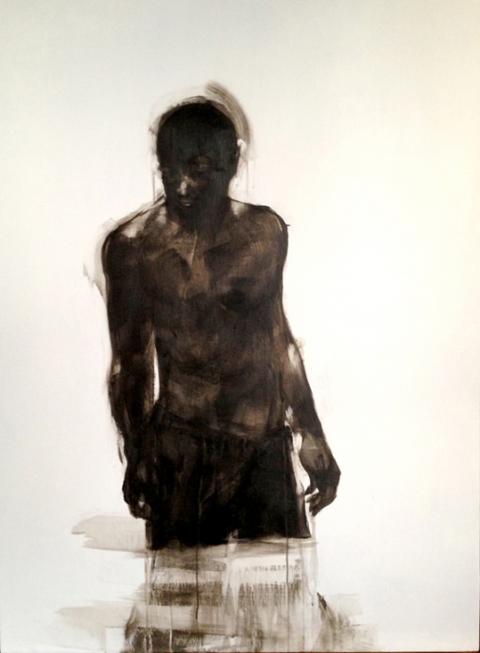

Judge’s remarks: Belinda Griffiths “The Turn of the Tide”

Having grown up in Ngataringa Bay in Devonport, where the mudflats and mangrove estuary were a happy playground, it was easy to appreciate Griffiths’ mud-smeared figure, mired and immobilised as the incoming tide threatened to engulf him; and while doing so, to also remember the mangrove ooze as a benign playground. What seems interesting to me that as a metaphor of our relationship to nature, it points to complexities and raises more questions, rather than providing easy conclusions or simple call to action. Are we helpless in the face of a rising tide of pollution; are we stranded and feeble in the face of the vast untameable chaos of the natural world; or both? What I like here is that the painting doesn’t try to answer these questions; nor does the artist in her statement. The questions are posed, for each of us to wrestle with and perhaps debate; and all the while, we may do so in front of a painting that is so beautifully conceived and executed that it has the power to still our thoughts; to calm our nerves; and to mesmerise us.

The sensual power of this painting is such that it also undercuts, or contradicts its own conceptual origins: no longer simply a young man about to be rescued before tide-rise and night-fall, he is physically and perhaps spiritually “one” with the mud; still; meditative; calm. “The Turn of the Tide” is a satisfyingly complex work that neither romanticises nature nor demonises us. We are in this together – muddy, wet, sun-drenched, mired, and moving.

Judge’s remarks: Bernie Harfleet “The Story of an Estuary”

Harfleet’s work touches on the deep pathos of remembering things past. It is also a comment on our attempts to hold onto the past through collecting and arranging objects of significance. What I find interesting in “The Story of an Estuary” is that it points to the fact that the objects we collect as relics of the past always fail in some way. They are not the same as what we have lost; they do not bring back the past; and they always only ever tell part of the story. Yet Harfleet’s work is also lovingly, and sympathetically disposed towards our human desire to remember what we have lost, almost by any means: a stuffed animal; an ornament; a bleached skull; a story book.

By carefully arranging the ornamental boats, shells, a stuffed bird and bird skulls, kete (woven bastet), folk-Maori lamp, kiwi and A. H. Reed’s 1945 publication “The Story of New Zealand” on a mid-century fireplace mantle, Harfleet is telling the story of a specific estuary: the Tamaki Estuary. For instance the stuffed bar-tailed godwit is an obvious reminder of the godwits that frequent the sand spit at the mouth of the Tamaki Estuary in the Tahuna Torea Nature Reserve. But his tableau is also generalised and we may recognise it in similar arrangements of memento mori in domestic sitting rooms, clubrooms and museums throughout the country. This relationship between the specific and the general is one of the powerful aspects of Harfleet’s work. Namely that while artists may use very particular, localised and quite personal material in their works, the best artists take these specifics and universalise them in such a way that they become accessible and meaningful to the many. Here, the Tamaki Estuary godwit becomes the idea of the extinction of all our birds; and in this, the work speaks to the situation of the Estuary Art Award, the challenge of the impending extinction of many species world-wide; and the very human dilemma of how to remember when we all know that memories are no substitute for the real thing.

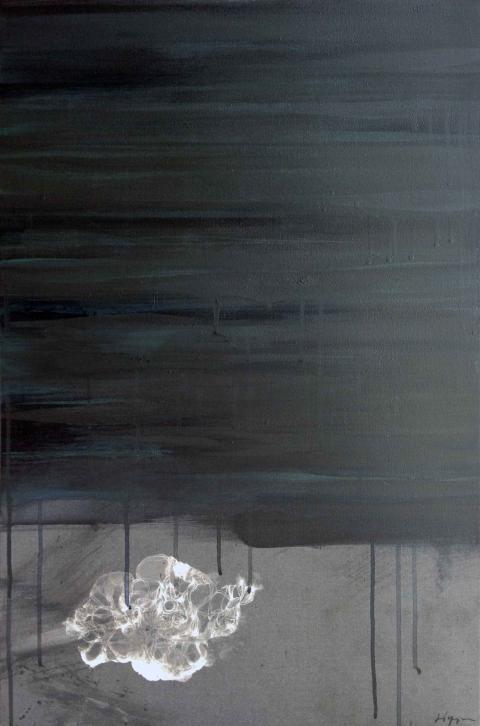

Judge’s remarks: Alby Yap “Phantom Soul”

Just like Belinda Griffiths, Alby Yap confronts the mud of the tidal flats head on. The painting is dark, sticky, dribbling and confronting. Yet it is also wonderfully nuanced. The black is actually a sensuous field of blues, greys, greens and browns. In his statement, the artist says the Estuary made him uneasy and haunted; yet he also acknowledges its beauty. His painting addresses the sticky stuff around the edges and underfoot as a fact and as a place where subtlety hides. The delicate white filigree of marks in the lower portion, which look a little like tube worms, is as delicate as a feather. Balancing the weight of the muddy blacks with this pale tracery seems effortless, yet it is not.

What interests me here is that the painting does not idealise the estuary; and thereby it does not idealise “Nature.” For Czech philosopher Slavoj Žižek this would demonstrate Yap’s true love of Nature; for, as the philosopher argues, “love does not idealise the other.” Why is this important in the context of the awards? Well, to quote Žižek again, “The way we approach the ecological problematic is the crucial field of ideology today; and I mean ideology in the traditional sense as the usual wrong way of perceiving reality. Ideology addresses very real problems but it mystifies them.” For me, Yap’s painting is interesting because of the way it addresses what lies at the artist’s feet – mud – in a very matter-of-fact way, in a way that refuses to prettify nature, and in a way that expresses his own unease. In a world where ideology presumes to have the answers, this black painting infers that things are not resolved; that they are uncertain.