A gaping hole

Collection of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw

In the Heart of the Country*

Over the past two decades, art has regularly surpassed reality by widening the horizons of the imaginable. Yesterday’s transgressions are the norm today, and the subjects art is delving into now could become our future. [Joanna Mytkowska, catalogue essay, p12.]

A highlight of spending several weeks in Poland in November 2013 to curate "Unearthing Delights", the 5th edition of Narracje in Gdańsk, was seeing the outstanding exhibition "In the Heart of the Country" in Warsaw, which was the first comprehensive presentation of the international collection of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw.

Here are five art works and projects from the exhibition which particularly attracted me through their aesthetic pull and their moving and profoundly intelligent connection to the everyday conditions of people. (The accompanying notes are courtesy of the exhibition catalogue.)

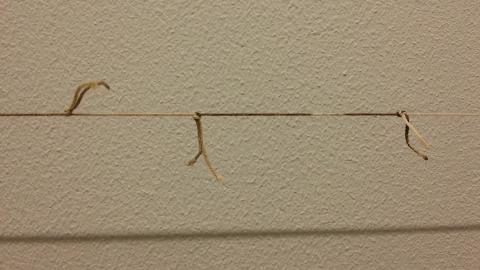

Teresa Margolles

127 Bodies, 2006

Installation-surgical suture threads

33.5 m

Teresa Margolles (born 1963, Culiacán, Mexico) is an artist working with installations, objects and films, and her main themes are violence and the media-flow of images of death in Latin America. The artist associates death with economic, political and social contexts, for example by scouting around for burial methods— especially mass, unmarked graves in Mexican slums—and ways of cremating or preparing bodies for post mortem examination. The artist’s works incorporate “relics” from victims of violence, gang wars, and drug cartels, e.g. water used to wash victims’ bodies in the dissection room.

One of Margolles’ most important works, “127 Bodies” was created for a solo exhibition by the artist at the Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen in Düsseldorf. It is a string over 33 metres in length, made up of 127 surgical suture threads that were used to sew up the bodies after performing post mortems on unidentified victims of street violence in Mexico City. This minimalist installation brings to mind works by artists like Mirosław Bałka or Alfredo Jaar, which humbly deal with tragedy and trauma. [Sebastian Cichocki]

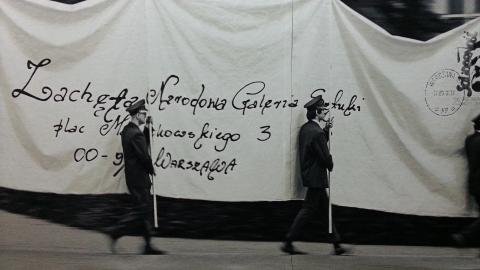

Goshka Macuga

The Letter, 2011

Tapestry

370 × 1132 cm

Goshka Macuga (born 1967, Warsaw) has lived and worked in London for many years, and was nominated in 2008 for a Turner Prize—the most prestigious award in British art. She uses a method described as cultural archaeology: each of her projects is preceded by in-depth archival and historical research, which allows her to reveal the broader context of the phenomena in question. She creates installations which include works by other artists, archive materials, and ready-mades, as well as her own objects, and thus she combines the roles of artist and curator.

“The Letter” is a tapestry over ten metres in length which depicts a reconstruction of Tadeusz Kantor’s 1967 happening of the same name. However, Macuga’s gigantic “letter”, carried by eight postmen, is addressed to the Zachęta Gallery, whereas Tadeusz Kantor’s message was sent to the Foksal Gallery. The context here is the history of the Zachęta Gallery, especially in the tempestuous last decade of the 20th century, when contemporary art ignited protests and aggressive reactions (e.g. Daniel Olbrychski’s “sabre-charge” against Piotr Uklański’s work “The Nazis”, or extreme-right parliamentary deputy Witold Tomczak’s destruction of a Maurizio Cattelan sculpture). During those years, the Zachęta Gallery received many letters containing brutal assaults on modern art, the gallery’s staff, and its then director, Anda Rottenberg. Some of those attacks were of an anti-Semitic nature. Goshka Macuga’s work came to commemorate the struggles of people from the art world, as well as the changes in a society which had to give up its prejudices, and work through its fears in order to accept artistic freedom. [Joanna Mytkowska]

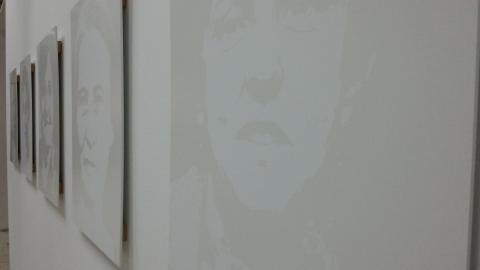

Sanja Ivekovic

Invisible Women of Solidarity, 2009-2010

Digital prints

Various dimensions

Sanja Iveković (born 1949, Zagreb) is a Croatian conceptual artist who has created sculptures, installations, photographs, films, and performances. A pioneer of feminist art in former Yugoslavia, one of the artist’s current themes is the situation of women in Central and Eastern Europe following the regime change.

This project was commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, and concerns the way in which women involved in the “Solidarity” liberation movement have been marginalised in Polish historical narrative and politics. In her desire to produce “a monument to the invisible women”, the artist concentrated on private narratives that were never part of right- or left-wing discourse in contemporary Polish politics. One of Iveković’s first actions was to “appropriate” the cover of “Wysokie Obcasy” (‘High Heels’) magazine, the women’s supplement to the “Gazeta Wyborcza” daily. It showed a modified version of Tomasz Sarnecki’s famous poster used during Poland’s first free elections in 1989—referencing the Western “High Noon”, Gary Cooper was depicted holding a ballot paper instead of a revolver—whereas Iveković’s version of the poster featured the silhouette of a woman. Another part of the project involved publishing—in a “pictorial” issue of “Krytyka Polityczna” (‘Political Critique’) magazine, designed by Artur Żmijewski and Maurycy Gomulicki—portraits of women who were engaged in opposition activity but, says Iveković, were later erased from the collective memory. [Sebastian Cichocki]

David Ter-Oganyan

Democracy, 2007, print on canvas

Nagorno-Karabakh, 2011, oil on canvas

Silhouette II, 2009, oil on canvas

Riots, 2009, oil on canvas

Works from the “Fight” series, 2009, 4 colour prints on canvas

David Ter-Oganyan (born 1981, Rostov-on-Don, Russia) is based in Moscow, and is one of the few Russian artists of the younger generation to have achieved international acclaim. He was involved in the “Ostalgia” exhibition at the New Museum in New York, and has a DAA D Scholarship in Berlin. His work deals with the situation of political oppression in Russia, and how artists are committed to public life.

In the late 1990s, when still quite young, David Ter-Oganyan became active as part of the Radek group, which was involved in public protests. Using that experience in the new political situation, which is considerably more oppressive towards artists, he is now very active in Moscow’s independent art scene. His work successfully incorporates a wide range of techniques and formats: oil painting, graphic art, film, video animation, and installations. He combines committed political diagnosis with innovatively fresh visual experiments. The Museum collection contains a selection of his more recent works, which focus on portraying street protests. The paintings and prints are arranged like a collage, which is typical for the artist and suggests a rapid-response, reportage-style capturing of reality. [Joanna Mytkowska]

Paweł Althamer

Barge-Haulers, 2012

Plastic strips on metal construction

170 × 150 × 1000 cm

Paweł Althamer (born 1967, Warsaw) is one of Poland’s most famous artists worldwide. His work has contributed to redefining the concept of “social sculpture”. He employs a wide range of techniques and methods, working in figure sculpture, as well as social actions and performance. He is known for being uncompromising and loyal to his artistic vocation.

“Barge-Haulers” is a piece inspired by the Museum’s own current situation— a constant struggle to build its own building in order to consummate its existence and secure a place for contemporary culture in society. Althamer alludes to the well-known painting “Barge-Haulers on the Volga” (1873) by Ilya Repin, one of the first Russian realists to couple realistic representations with an affinity for the common people. Paweł Althamer’s sculpture, made using the artist’s own special technique, contains the figures of the first eleven members of the Museum team (recognisable from plaster-casts of their faces), who—like barge-haulers—are straining as if there were no tomorrow, as they drag a model of the Museum that will be built one day. This group of sculptures is a unique part of the Museum collection. Not only does it document a heroic period of the institution’s existence, expressing support for efforts to create a museum of modern art in Warsaw, but it also reveals the artist’s strong convictions about the social role of art. [Joanna Mytkowska]

Artists:

Paweł Althamer, Francis Alÿs, Mirosław Bałka, Yael Bartana, Wojciech Bąkowski, Miron Białoszewski, Cezary Bodzianowski, Geta Brătescu, Ivan Brazhkin, Wojciech Bruszewski, Michał Budny, Rafał Bujnowski, Duncan Campbell, Olga Chernysheva, Anne Collier, Abraham Cruzvillegas, Julia Dault, Oskar Dawicki, Nathalie Djurberg, Jimmie Durham, Bracha L. Ettinger, Ruth Ewan, Omer Fast, Yona Friedman, Ion Grigorescu, Aneta Grzeszykowska, Wiktor Gutt and Waldemar Raniszewski, Sharon Hayes, Jonathan Horowitz, Sanja Iveković, Ken Jacobs, Zhanna Kadyrova, Polina Kanis, Leszek Knaflewski, Daniel Knorr, Prof. Grzegorz Kowalski’s Workshop Archive, Wojciech Krukowski and Akademia Ruchu, Paweł Kwiek, KwieKulik, Zbigniew Libera, Klara Lidén, Sarah Lucas, Goshka Macuga, Teresa Margolles, Adrian Melis, Gustav Metzger, Aernout Mik, Teresa Murak, Laurel Nakadate, Deimantas Narkevičius, Krzysztof Niemczyk, Paulina Ołowska, Ewa Partum, Dan Perjovschi, Pratchaya Phinthong, Marek Piasecki, Seth Price, R.H. Quaytman, Joanna Rajkowska, Mykola Ridnyi, Józef Robakowski, Bianka Rolando, Wilhelm Sasnal, Jadwiga Sawicka, Jacek Sempoliński, Wael Shawky, Ahlam Shibli, Slavs and Tatars, Jack Smith, Roman Stańczak, Frances Stark, Jan Styczyński, Alina Szapocznikow, David Ter-Oganyan, Teresa Tyszkiewicz, Piotr Uklański, Zbigniew Warpechowski, Helena Włodarczyk, Krzysztof Wodiczko, Andrzej Wróblewski, Akram Zaatari, Stanisław Zamecznik, Anna Zaradny.

*There is a gaping hole in the heart of the country.

The geographic centre of Poland, Warsaw city centre, lies empty. Plac Defilad (Parade Square) is abandoned: once a symbolic hub, the Palace of Culture is now surrounded by deserted space, a makeshift car-park. Among the cars the honorary tribune still stands, left behind from the days when May Day processions used to march past it. The crownless eagle that adorns it now watches over travellers exposed to the sun, rain and wind as they wait at the temporary bus station. This is where the Museum is to be built, and its collection has a mission to fill the void in the heart. [Joanna Mytkowska, catalogue essay, p11.]