Breathtaking

Between the everyday and a dream

inSPIRACJE 2017

Trafostacja Sztuki / Trafo Centre for Contemporary Art, Szczecin, Poland; 30 June - 30 September 2017

Artists:

Tereza Buskova (CZ-UK), Cathy Carter (NZ), Jordi Colomer (SP), Matthew Cowan (NZ-DE), Anne Ferran (AU), Zuza Golińska (PL), Eva Grubinger (AT-DE), Weilun Ha (VT-NZ), Paweł Kleszczewski and Kasia Zimnoch (PL-IR), Aurora Lubos (PL), Jarek Lustych (PL), Ed Osborn (US), Bartłomiej Ponikiewski (PL), Eliza Proszczuk and Łukasz Kowalski (PL), Shana Robbins (US), Caroline Rothwell (AU), Robert Smithson and Nancy Holt (US), Katarzyna Swinarska (PL).

Venues:

Trafo Centre for Contemporary Art (Trafostacja Sztuki w Szczecinie) and Galeria R+ (Art Academy of Szczecin), plus site-specific projects in public spaces.

The Curatorial Themes

Breathtaking – Between the Everyday and a Dream

Szczecin is re-positioning itself as a meeting place for creative minds, innovative thinkers and technology experimentation. Its rebranding is poetic and mysterious: Floating Garden. This idea already has its roots in life and creativity. First there are the centuries-old floating gardens (Chinampa) created by the peoples of the central lake system of Mexico; and it is an idea that has taken form in artists’ works, most notably Robert Smithson’s Floating Island (1970-2005).

The idea of Szczecin attracting innovative thinkers under the evocative notion of a floating garden; together with Szczecin’s port character, nearness to the former Western Europe and emerging multi-culturalism; and the sense of possibility evoked by its wide open urban spaces and boulevards have captured my imagination and influenced my thinking. The art projects of Breathtaking: inSPIRACJE 2017 Festival are characterised by gallery exhibitions as well as public sites outside the gallery.

Breathtaking brings attention to Szczecin’s watery character and history; and to breath as a shared life force. Breathtaking gathers ideas and experiences as diverse as floating, sinking, thirst, taking breath, inspiration, water gardens, living on the river, rising water levels, flood plains, environmentalism, post-industrial riverine landscapes, borders, migrations, bodily and social rituals, bathing and watery wildness.

Three visual motifs underlying Curatorial theme

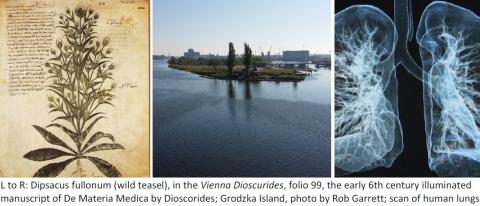

Teasel / Szczeć (Dipsacus fullonum)

The festival’s relation to the city of Szczecin comes in part from one of the stories of the origin of the name Szczecin. One of the several stories of origin suggests there might be a relationship to the Polish word for the plant Wild Teasel (Dipsacus fullonum) – Szczeć. In turn, the plant's genus name Dipsacus comes from the Greek verb 'to thirst.' The Teasel plant first acquired this name because it is in fact a thirst-quencher: the structure of the plant is such that a natural cup-like formation grows at the base of the flowering part of the stem and just above where the leaves-proper form. Water naturally collects in cup-like structure and thus the plant attracts all those who are thirsty. Water’s regenerating and refreshing properties – and the relation to plants – are thus obliquely celebrated in the name of Szczecin.

Grodzka Island / Wyspa Grodzka

The island of Grodzka is a powerful symbol of the life-giving properties of Szczecin’s waterways, right in the heart of the city. It is a raft of gardens and is usually witness to the city’s human and avian fisher folk who daily visit the River Odra in search of a meal. Szczecin, like many Polish cities, has retained a good number of garden allotments (ogródki dzialkowe) where citizens grow their own fruit and vegetables. This is a very old tradition with origins at least in the development of walled towns in Medieval Europe in which town residents had gardens or plots of land for growing their food close-by, but usually outside, the city’s fortifications. The modern allocation of garden plots in Poland commenced in the late 19th century (around the suburban fringes of cities; and was first legislated in the second Polish Republic after WWI; and again between 1945 and 1950 there was a strong urban gardening movement to help the working class overcome constant food shortages and to reduce political complaints. In Szczecin allotments on Grodzka Island were given to the families of the ‘best workers’ from the shipyard. After 1989 some of these stayed in the same families while others were sold off. Across Poland, by 2008, there were about 960,000 individual plots (covering 44,000 hectares), meaning one plot for every ten households. The allotments on Grodzka are a powerful symbol of urban balance between green-space and development; a symbol of self-reliance; and a concrete example of post-capitalist economics.

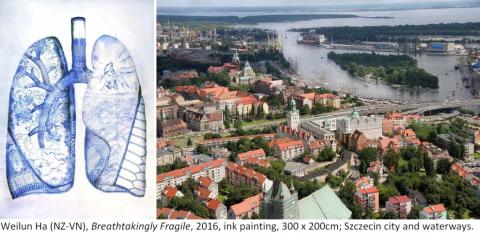

Lungs / Płuca

Finally, a personal story involving my mother (Edna Lois Garrett, 1926-1992) that partly explains how I come to be drawn to the waterways of tidal estuaries, river deltas, swamplands and small islands – often neglected, stinky, waterlogged, muddy and inconvenient – as powerful metaphors for creativity, hopefulness and renewal. As a young woman my mother contracted tuberculosis and in her day, the treatment, which was rarely successful, involved removing all the parts of the lungs and rib-cage to which the disease was attached. Miraculously the 20-year old survived and went on to marry and bear four healthy children. All my young life I lived with an uncomplaining yet short-of-breath, vigorously inquisitive and optimistic woman – my mother. Though she had ‘suffered’ a cure which included the total removal of one lung, the partial collapse of the other and the removal of quite a few rib bones, she survived into her 60s… Growing up in this environment it was impossible for me to ever take breathing for granted! Coincidentally the family grew up on the shores of a wonderful tidal estuary in the inner harbour of Auckland city in New Zealand. The place was abundant with fish and bird-life and formed the backdrop and the playground for our young lives. The mud of the tidal flats stank horribly at low tide in the humid sunlit intensity of New Zealand summers; but I had first-hand experience of how these muddy, oozing sand flats, surrounded by mangrove forests, were in fact the nursery for all aquatic and birdlife in the harbour. For some strange and yet now obvious reason, these nurturing mangrove swamps and the image of human lungs – delicate, full of tributaries and often over-looked – became entwined as one powerful metaphor. Now, Szczecin’s reed-fringed and sometimes swampy waterways have become entwined with this picture too.

FLOATING: Tension between the everyday and a dream

The idea of floating contains the possibility of rising above something; of being buoyed along with the tide or rising above the flood. But this optimism is also always paired with the threat of disaster or tragedy – island nations sinking below the rising ocean; boat-loads of desperate migrants being tipped into the sea; or inexperienced swimmers sinking beyond help. The euphoria of floating is perhaps heightened by our consciousness of this delicate balance between safety and terrible danger. Floating and drowning go hand-in-hand. There are both pleasures and pitfalls in launching our vulnerable bodies off terra firma [dry land] into rivers, lakes and oceans. Whether we are swimming, paddling or sailing we must connive with the water not to be consumed by its vastness and defeated by our heaviness, by gravity. We must be clever and light.

AIR: Breathtaking

The theme ‘Air’ captures the twin necessities of ‘air to breathe’ and freedom of thought – the freedom to dream the impossible. The sharing of breath in some cultures also is a reminder of the very origins of life (Maori ‘hongi’ pressing of noses) and in others evokes the most intimate bonds of friendship and love (the kiss). It is a theme which seeks to ground inSPIRACJE in the real and the imagined, the necessary and the visionary. It is an aspect which also takes ‘inspiration’ from the Festival title too – inspire – to breathe in.