Insistent Communities

The limits of art; the failure of institutional practices; and the necessity for action

"The more you press, the bigger it gets" (Gezi Park stencil, 4 June 2013).

In the present context of citizen activism and Occupy Movements that call for people's greater participation in public politics, what is the role of contemporary art in the public realm?

There's been a wave of 'activist art' surveys exhibitions and biennials in recent years and along with them, much criticism, or at least skepticism about the value and effectiveness of so-called art activism. Well, I've recently been more interested in the impact of activism on art; and along with many of the skeptics, would like to think about important differences between three things: critical art, activism that happens to use aesthetic means and political action. For me, the first and the last are spheres of activity that overlap a little to constitute the middle term: aesthetic activism. But these interests are really a bit of a side-bar to my real interest; namely an interest in the likely impacts of contemporary political and cultural activism on contemporary art itself, and more precisely on the art that takes place in public institutions and in the public realm where I believe it is becoming more and more difficult to be blind or deaf to communities insisting on participation; expecting an end to exclusionary policies and systems; and demanding the elimination of inequalities wherever they are found.

Citizen activism and occupation of public space is not new; but the speed with which the various manifestations of the Occupy Movement and diverse citizen uprisings in the past few years mobilised and multiplied, coupled with their often heterogeneous character (multi-ethnic, multi-faith) is somewhat new and different.

Admittedly the speed and size of these and other recent mobilisations owe a lot to the way ordinary people and grass roots communities can disseminate information and ideas very quickly and widely through social media communications; but this may in fact be over-emphasised. Probably the mobilisation and diversity owes more to new notions and expressions of the collective - of the "being-with" as a mutual exposure to one another that preserves the freedom of the "I", and thus a community that is not subject to an exterior or pre-existent definition [after Jean-Luc Nancy Être singulier pluriel (Being Singular Plural, 2000)]. Within this reformulating sense of the communal there is also what I would call a 'passionate pragmatism' which manifests itself as a politics of tactical coalitions focussed on key common demands for equality and freedom while other demands around which there may be less unanimity can be set aside for a time. The heterogeneity of these movements and moments also demonstrates the way diverse groups of people who feel in some way systematically and structurally exluded, disenfranchised or otherwise moved by inequity, can - and will - join what, at first sight, seem like quite narrowly focused protests when they perceive these to be connected to or emblematic of wider issues of social inequality and political exclusion.

Thus, we are seeing activist communities define themselves both in terms of their own particular interests; and in terms of an overarching aspiration for full participation in the public realm and greater social and economic equity. The inverse lesson of course, is that any localised node of elitism, structural exclusion or systematic inequality is less and less likely to be able to hide within its local sphere of influence for long. Instead; as soon as any resistance to the local is mounted it is likely to quickly become the focus of very widespread interest and the object of very heterogeneous activism.

What is the urgency for the cultural sector?

The cultural sector straddles both sides of the dividing line that is formed in the moment of protest or activism. On the one hand, aspects of the cultural sector act and / or are perceived as acting, in alignment with power elites that structure exclusions and enshrine inequalities. On the other hand, artists and other creative workers share much with protestors who imagine and strive for a more inclusive, equal and participatory world for themselves. The urgency for the cultural sector exists in the degree to which it persists to be associated with the 1% (for instance, of the Occupy Movements) as an example of a sector that is habitually associated with spendthrift elitism. Paradoxically, it is the creative workers of the cultural sector who possess one of the most powerful tools of the 99%: unfettered imagination. The cultural sector can probably quite rightly to be adjudged part of the problem as much as it can be claimed to be part of the solution. Only the particular relationships forged and actions taken within particular contexts will determine on which side of this line the cultural sector, or forces within it, will stand, or be perceived to stand.

Rachel Jane Liebert (NZ/US) eloquently expresses the importance of the imagination when she writes it "is not a question of what art can do for (r)evolution, reducing it to a vehicle for a message, making it hollow. Art is (r)evolution. As the doing of imagination, it is pre-figurative politics at its most beautiful & subversive. And, in a world where protest is increasingly imprisoned, diagnosed, shamed – immobilized through prisons, drugs, norms – labeled Terrorist, Patient, Deviant – doers of imagination are more needed than ever."

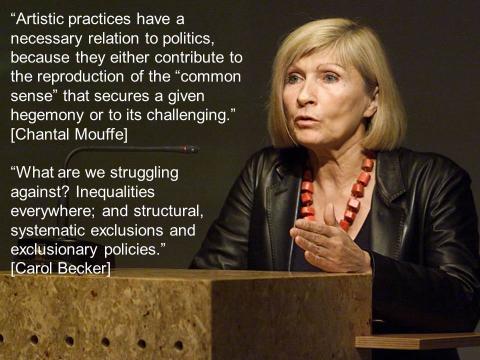

I am also inspired by Carol Becker's thoughtful considerations about the nature of cultural citizenship, micro actions and the power of ideas.

Really what choice do any of us have than to work for a "better world," as you say. How else can we live in this world but to work to improve it? I guess I simply don't understand how else to function. What else would we do? And, why would we give up? There is no giving up. Wherever we are, in whatever way, we have to try to change inequity, to help each other not to suffer. It's the human project and everyone can participate in it - no gesture is too small. [2013 interview by Alexandra Epp and Grace Pollock]

Actions needn’t last forever to be effective. Just the fact of their existence affects consciousness and the possibility of humans to rethink their relationship to each other and to the State. It’s not a failure when such movements [as the Occupy Movement in the U.S.] devolve; I would say rather it is a triumph that they exist at all. Once ideas come into society they cannot be permanently erased and their existence, if only brief, still gives hope. Artists understand this, which is why they can be so essential at such times. [2012 interview by Georgia Kotretsos]

How am I approaching this question?

My first interest is in the relation between the political and art; not from the perspective of art about politics, or so-called ‘political art’; but in what it is about art that has the greatest political potential, namely that every art work is a concrete reminder that a person exercised their unfettered imagination; and by keeping alive this notion of the unfettered imagination, art, by its very existence can remind people of the life and the power of the imagination which is so necessary in order to conceive of changing our world. This notion draws on the work of cultural theorist and art critic bell hooks who wrote that "regardless of subject matter, form, or content, whether art is overtly political or not, artistic work that emerges from an unfettered imagination affirms the primacy of art as that space of cultural production where we can find the deepest, most intimate understanding of what it means to be free." [bell hooks. 1995. Art on my mind: Visual politics. New York: The New Press, p.38]

Secondly I am interested in how people engage with art, and how art can make authentic engagements with people’s social reality. These interests are profoundly informed by my past activities and experiences. Initially, while I was still practicing as an artist, by work was primarily unofficial performances and temporary installations in the public realm. Later, as a researcher, writer and teacher in academia I was interested in the historical and theoretical underpinnings of art in the public realm; in the theoretical tools that could help us think about art practices that aspired to engage with and influence the real social and political situations people found themselves in; and pedagogically questions about how the Art Academy could best prepare its graduates for an engaged practice. In more recent years as I have been asked by various city governments to assist with public art policy and planning, I have been engaged with the question of how to ensure that city-commissioned public art activity can be both art driven and fundamentally more community-engaged and democratic in process. As a curator, most often of site-specific public art programs and projects, these same questions take on a very concrete and pragmatic dimension; and they intersect with an urgent desire to have public art activity grow out of a well-grounded engagement with the real situations of ordinary people.

My reflections on the need for wider and deeper community engagement in contemporary art in the public realm have been stimulated by recent instances of political protest as well as by instances where I have either witnessed or participated in art projects that have sought to engage with people's real situations. Considering the contingencies of our time, marked as they are by a burgeoning trend for participatory culture and political activism - demonstrated by various citizen-led activist movements, including calls to boycott major visual art events for their association with inequalities and structural exclusions - I remain inquisitive to know what sorts of cultural participation will meet the needs of these and yet-unknown “insistent communities”? What can be learned from projects and actions in places as diverse Taksim Square in Istanbul, Turkey; bombed and burnt out ruins in Gdańsk, Poland; Biennale troubles in Sydney, Australia; a Mexican / Puerto Rican / Central and South American neighbourhood in Chicago’s West Town; the rural Australian town of Mildura; a brown-fields development in downtown Auckland, New Zealand; and community committees commissioning public art in France.

“Insistent Communities” is based on lectures I presented in 2013 and 2014 at Mildura Palimpsest #9 Symposium (Mildura, Australia); La Trobe University (Melbourne, Australia); AUT University of Auckland (Auckland, New Zealand); Gdańsk Art Academy (Gdańsk, Poland); and La Station Contemporary Art Centre (Nice, France). My thinking in this area of interest continues to evolve; and the present collection of opinions and thoughts owes much to the generous collegial discussions I was privileged to benefit from in each location.

During June 2013, the Occupy Gezi Movement emerged as the greatest challenge to Prime Minister Erdogan’s decade-long rule in Turkey. In the streets and in Gezi Park, as well as through its widespread use of social media and its various aesthetic tools.

Christiane Gruber made very useful analyses of the visual forms and tactics that became central to the Occupy Gezi Movement. Her writing included the following emblematic observation: The demonstrations spread beyond the initial environmental sit-in in Gezi Park when tents were burned and a woman wearing a red dress was teargassed by a police officer. The brutal chemical attack left her gasping for air and caused her to collapse on a bench. It has since come to light that this woman is Ceyda Sungur, a faculty member specializing in urban planning at Istanbul Technical University. She, her colleagues and students, and other concerned citizens had been arguing that Istanbul needs green “lungs” to breathe. Sungur’s image became one of the main icons of the Occupy Gezi movement. [Christiane Gruber, "The Visual Emergence of the Occupy Gezi Movement" (parts One, Two & Three)]

For me, other moments of what I would term ‘aesthetic activism’ stood out too, because while they were clearly in the realm of activism - not 'art' - their conception and concretisation were the result of the aesthetic sensibility and the knowledge and experience of creative individuals.

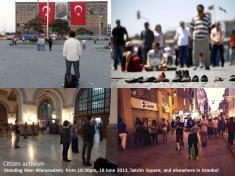

Like a dance project, but not a dance project: 'Standing Man' / #duranadam of 17 June 2013 is an example of aesthetic activism within the incredibly diverse modes of protest deployed in and around Taksim Square in Istanbul, Turkey

One of the most striking images that appeared for me as I was following the Gezi Park and Taksin Square protests unfold, from Auckland, New Zealand, was that of 'Standing Man' - quiet and still, impassive, immovable - facing the Ataturk Cultural Centre.

What struck me was the way this figure embodied the idea of a powerful resistance to government and police violence in that he gave off no physical energy that might then be turned against him. That day, there even emerged a video clip online that revealed, even in the first few minutes, police had approached him and checked his bag, searched his pockets and found nothing, and had to leave him alone as he was not really protesting actively. Everything about his passivity and the neutral emptiness of his bag even, gave off nothing that the repressive forces could feed off and become energised with. I thought, here is a perfect gesture accompanied by a great consciousess of the perfect embodiment of the word 'No!'

Only later did I discover that this man was Erdem Gündüz, a choreographer; a fact which confirmed my suspicion that he knows the body's gestures and energies and deeply understands the power of movement or non-movement to catalyse an audience's own energy, movements and feelings. Here he harnessed the power of immobility to create a great power capable of absorbing negative forces; standing for 8 hours from 6:00pm until he was arrested for refusing to move. In this time he was spontanteously joined by at least 300 others.

He created, perhaps unwittingly, but also perhasp not, of a figure in space - not one of many, one of a crowd, one of a phalanx or line or cordon. One in space.... and it was this composition of gestures that was quickly replicated by the others who joined him in Taksim Square and elsewhere in public spaces - neighbourhood streets, train stations, the law courts atrium - across Istanbul. Even after his arrest, across Istanbul, figures appeared, each composing themselves in the same manner: separated from one another by a space of dis-connection (non-association) - thus not forming a crowd, a group, a gathering - and standing still, some reading, some with a water bottle; and each with a bag empty of all but 'innocent' items lying at their feet.

Erdem Gündüz, with his formal knowledge of the aesthetics of the body entered the Square as a cultural citizen and enacted a form of political resistance, or aesthetic activism. In my opinion, despite his profession, he did not perform an artwork; but the aesthetic and performative means he used enabled the gesture and the power of the action to be instantly understood and reproduced in person, in graphics and as the embodiment of an idea with its own hashtag: #duranadam.

Like an art project, but not an art project: The fashion district bands together for an aesthetic protest action in Galata Square, Istanbul, 19 June 2013.

Remeniscent of any number of contemporary art installations using the repetitive patterning and symbolism of items of clothing, including shoes, laid out en masse, Istanbul's fashion district protest the day after protestors in Gezi Park met with violence, evoked not only the aesthetics and formal language of the art gallery, but also the symbollic language of protest itself - suggesting the vigil of 'standing man' in Taksim Square of the day before; the empty shoes of Holocaust victims; or even the throwing of shoes in protest, perhaps made most famous after Muntadhar al-Zaidi threw his shoes at then U.S. President George W. Bush in a 14 December 2008, press conference in Baghdad, Iran.

We can see what happens when artists engage as everyday citizens in political struggle, but what happens when artists take on their own institutions?

I had been thinking that it was only a matter of time before the values and energy embodied on the 'Occupy' and 'We are the 99%' protests would direct themselves to to the artworld. While many might say that artists and the idea of free imagination that they seem to embody might generally be perceived to be a part of the answer to social inequalities and political injustices; and that the real wages that most artists enjoy, and the relative lack of capital ownership held by artists, certainly place them well within the 99%; it would also be easy for any reasonable person to associate many art institutions, including the ostentation of auction houses and art fairs, the privilege of many of the art world's sponsors and benefactors, and the huge capital wealth amassed by a few (with their art collections, art parks and art buildings) firmly within the 1% camp. [Regarding the distinction between 'income' and 'capital' for instance, French economist Thomas Piketty's argument about the danger of the rising inequality of recent decades is based precisely on understanding this distinction.] I felt it would only be a matter of time for a new wave of protests aimed at biting the hand that feeds them to emerge among cultural citizens. I wondered what this wave of political action from the creative sector might look like?

There were already examples of course. The Liberate Tate movement in the UK dedicated to taking creative disobedience against Tate until it drops its oil company funding has made progress; but neither the Tate nor BP have been stopped in their tracks. Would something equivalent to the disruption of the Occupy Movement and its power to reconfigure public discourse emerge in the artworld?

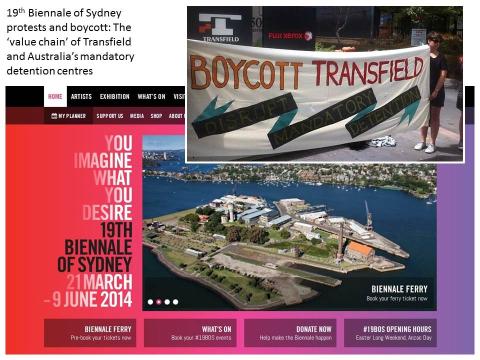

It transpired that 2014 may have been a watershed year for the arts; and in small part, my wondering was answered when artists took aim at the 19th Biennale of Sydney for its dependence on funding linked to Australia's mandatory detention centres with their track record of human rights abuses.

In 2014 calls were made by refugee activists for artists and others to boycott the 19th Biennale of Sydney (21 March – 9 June 2014) in response to the perceived 'chain of connections' between the Biennale, Transfield Holdings and Transfield Services, and the latter's contract with the Australian Department of Immigration for the building and management of Australia’s offshore mandatory detention centres for asylum seekers on Nauru and on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea.

The Australian government’s approach to asylum seeker policy, which includes the offshore processing of those who arrive through ‘unofficial channels’, is widely regarded as draconian. A bipartisan reality, it has been condemned as contravening national obligations as laid out in the 1951 Refugee Convention, as well as a variety of international human rights laws. In addition, Transfield recently won a contract from the Australian government to take over the management of garrison and welfare services in these detention centres, meaning that the one company manages detainees’ housing, security, transport, catering, cleaning, psychological and medical support. (Note that many detainees become psychologically disturbed and even suicidal during their confinement in such detention centres.)

On the 19th of February 2014, 28 artists participating in the 19th Biennale of Sydney published an open letter to the Board of Directors about their concerns with the sponsorship arrangement with ‘Transfield’. The 28 artists stated in their letter “We urge you to act in the interests of asylum seekers. As part of this we request the Biennale withdraw from the current sponsorship arrangements with Transfield and seek to develop new ones.” The group of artists who originally signed this open letter were Gabrielle de Vietri, Bianca Hester, Charlie Sofo, Nathan Gray, Deborah Kelly, Matt Hinkley, Benjamin Armstrong, Libia Castro, Ólafur Ólafsson, Sasha Huber, Sonia Leber, David Chesworth, Daniel McKewen, Angelica Mesiti, Ahmet Öğüt, Meriç Algün Ringborg, Joseph Griffiths, Sol Archer, Tamas Kaszas, Krisztina Erdei, Nathan Coley, Corin Sworn, Ross Manning, Martin Boyce, Callum Morton, Emily Roysdon, Søren Thilo Funder, Mikhail Karikis.

On 20 February 2014, 6 additional Biennale artists signed on to the open letter and by 26 February 2014 41 Biennale artists in total had signed this open letter. On 26 February 2014, five artists (Libia Castro, Ólafur Ólafsson, Charlie Sofo, Gabrielle de Vietri & Ahmet Öğüt) withdrew their participation in the Biennale of Sydney in protest. This protest was due to the artists' perception that ‘Transfield’ was profiting from the mandatory detention of asylum seekers and the Biennale's refusal to cut sponsorship ties with Transfield as requested by the artists. On 5 March 2014, four more artists (Agnieszka Polska, Sara van der Heide, Nicoline van Harskamp and Nathan Gray) withdrew their participation in the Biennale of Sydney.

In March, the Board of The Biennale of Sydney announced that it would cut ties with Transfield, following the growing criticism from artists and refugee activists. The majority of boycotting artists returned to participate in the 19th Biennale with the exception of Australian artists Charlie Sofo and Gabrielle de Vietri. [Sources: Wikipedia; and Helen Hughes, “On the Boycott of the 2014 Biennale of Sydney”, Frieze blog, 20 February 2014.]

There are several very good discussions of the boycott, its effects and its many complexities and ironies, on both ‘sides’ of the protest. Notwithstanding the misgivings many expressed about the inconsistencies inherent in a protest which boycotted only one aspect of Government funding of the abuse of human rights in the detention centres and the associated value chain – it could be argued for instance that artists boycott Australia Council arts funding for the same reasons – this was a moment when artists chose to act and speak as citizens in the name of equality and against injustice rather than just through their art, specifically so as to attempt to distance themselves from the idea of ‘sanctioned speech.’

And of course, as Patrick Stokes (Lecturer in Philosophy at Deakin University, Melbourne, Australia) observed, none of this will move the needle one bit on asylum seeker detention policy …. And yet.

And yet, a group of individuals stood up, at some cost to themselves, to withdraw their implicit support of a company that makes money from our brutalisation of the most vulnerable. And they won …. Whatever the complexities, and however limited the impact, there was, at least, a moment, here in 2014, where the idea that misery outweighs money won some sort of victory. It won’t change much. It won’t change anything at all for those suffering on Manus and Nauru right now. Some will call it merely symbolic, an empty gesture. But gestures matter. Symbols matter. [Source: “The Biennale, Transfield, and the value of boycott” by Patrick Stokes.]

Update, 2 December 2014: Biennale of Sydney Chairman Phillip Keir is hopeful Belgiorno-Nettis family will return as major donors to 20th Biennale after breaking ties with Transfield Services, which operates facilities on Nauru and Manus Island.

What happens when cultural organsiations make a step-change before there is any protest? Can policy address inequality? Chicago in the 1990s provides useful case studies on policy- and artist-led initiatives to redress representational inequalities and social exclusions.

One of the leading US philanthropy organisations, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, did just this. In the second decade of their existence [1988-1997], fuelled by growing assets as Mr. MacArthur's real estate holdings were liquidated, the Foundation undertook reviews of the results of its past donations to the arts in the Chicago area in light of its interest in fostering community and neighbourhood development efforts in Chicago.

While donations to Chicago’s major arts institutions were indeed worthy, they were found to support Downtown communities and a well-established white cultural elite and they failed to penetrate the African American and Hispanic neighbourhoods that characterised the city or to develop cultural inclusivity. Local arts and culture leaders were called upon by the Foundation to provide advice on how they could best make a difference [source: personal conversation with Carol Becker, 1996].

One of the results was the provision of funding for, and the explicit commissioning of, programmes of public art and community arts activities that reached into and actively engaged with the previously dis-engaged communities. The “Culture in Action” programme was one of the beneficiaries; and the project "Tele-Vecindario" (1992-93) by Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle is an exemplar of the programme's cultural and social aims. Here curator Mary Jane Jacob explains:

Tele-Vecindario (1992-93) was a project commissioned as part of Sculpture Chicago's Culture in Action public art program. The project's organizational processes sought to bridge the social and cultural isolation of residents of West Town, a neighbourhood of Chicago, and create a space for dialogue. Through the project, artist Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle aimed to transform and reclaim the neighbourhood street, territorialized by gangs, into a communal promenade. The project was centred in the artist's own neighbourhood of West Town, a predominantly lower-income, Mexican, Puerto Rican, Central, and South American neighbourhood. The usual urban problems—lack of jobs, high drop-out rate, crime, drugs, gangs, teen pregnancy, and AIDS—affect the area. Video emerged as "the very tool of the tertulia (conversation), the means by which a dialogue between peers and with adults could be facilitated." The project took the form of multiple video dialogues among neighbours, known cumulatively as Tele-Vecindario. A youth division of the project named Street-Level Video (S-LV) became a central force.

A Street Level Video Block Party was a major component of S-LV's multiyear work; an event encompassing one residential street, using seventy-five monitors, involving four rival gangs and S-LV members, with an audience of more than a thousand people. For 12 hours, video monitors were grouped in multiple installations. The event, both a block party and video installation, also included a stage with teen performers and a peace mural whose negotiated design involved S-LV, gang representatives, some neighbours, and graffiti artists. Insiders and outsiders to the neighbourhood blended as they strolled down the street for the evening's tertulia. They conversed with each other or listened to each other on videos. As the evening progressed, the monitors lit the street and provided, albeit ephemerally, a neutral site for cultural and social exchange.

Video itself emerged as the artist's tool for engaging the neighbourhood, enlisting students, meeting other people, and learning the terrain. Manglano-Ovalle visited more than 40 social service agencies in order to refine his approach to the project. The artist knew that active involvement of area leaders was essential to integrate this project into the life of the community. He formalized the associations and alliances he had been building over a year's time with the creation of a new coalition of youth organizations that called itself West Town Vecinos Video Channel. S-LV, now known as Street Level Youth Media, remains actively engaged in the community with a storefront location. It continues to hold an annual block party among its many programs. [Sources: Jacob, Mary Jane. Culture in Action, Seattle: Bay Press, 1995, p. 76-87; and interview, Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle. See also this interview with Mary Jane Jacob on the Chicago initiatives.]

Aside from aesthetic activism or political action, is it possible that there is a necessary relation between artistic practices and politics? The political theorist Chantal Mouffe, Professor of Political Theory at the University of Westminster, argues there is.

I have found her work very fertile ground for thinking about the potentialities of critically engaged artistic practices in the public / political realm. Key among Mouffe's arguments are two thoughts about the relation of cultural production to politics.

First there is her claim that “artistic practices have a necessary relation to politics because they either contribute to the reproduction of the common sense that secures a given hegemony or to its challenging.” [Chantal Mouffe, “Artistic Strategies in Politics and Political Strategies in Art” par.9]

Second, Mouffe argues that given the former, “what is needed is the widening of the field of artistic intervention by intervening directly in a multiplicity of social spaces, in order to oppose the programme of total social mobilisation of capitalism. The objective should be to undermine the imaginary environment necessary for the reproduction of capitalism.” [Chantal Mouffe lecture “Agonistic Politics and Artistic Practices” at the Glasgow School of Art, 2 March 2007; audio only; 4:20–5:00mins.]

Her advice about how this might be done – with the strict qualification that critical artistic practices are neither the same as political action nor sufficient in themselves to bring about a new hegemonic order; and in fact, in the construction of this new order, the strictly political moment cannot be avoided – is that critically engaged artistic practices are particularly powerful in being able to show that “things could have always been otherwise” and thus challenge the common sense upon which hegemonies are built and persist by undermining the imaginary environment.

The arts are also powerful means by which alternatives to the dominant power régime (its structures, rhetoric, élites and consequences) can be understood: the arts can articulate new imaginary environments; mobilise affects; construct new subjectivities; and give voice to what is silent in the given hegemony. [Lecture at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, Germany, Friday, 9 October 2009]

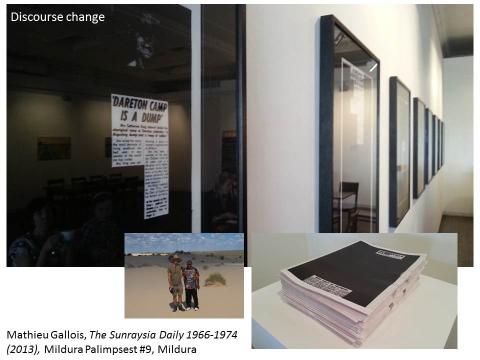

An artist works closely with the local indigenous community to articulate an historic shift in the way “white fella” newspapers in Australia and Britain portrayed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia.

Mathieu Gallois’ The Sunraysia Daily 1966–1974 (2013) articulates an historic shift in the hegemonic discourse of mainstream Australian culture towards the country’s indigenous peoples. Through the lens of one town’s daily newspaper, the project documented how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia were historically portrayed in “white fella” newspapers in Australia and Britain. It was undertaken in close consultation and partnership with the local indigenous peoples; and was presented as a part of Mildura Palimpsest Biennale #9, October 2013.

Artist Statement:

The Sunraysia Daily 1966 – 1974 documents key articles relating to Aboriginal affairs and race relations in Mildura’s local paper, the Sunraysia Daily, between 1966 –1974.

The period 1966 – 1974 includes the 1967 national referendum and the discovery of Mungo Woman and Man. The former amended the Australian constitution to count Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians in the national census of the population and to give the Commonwealth Government power to make specific laws for Indigenous people. The latter established Australian Aboriginal culture as humanities oldest continuous culture (more than 40,000 years old).

The Sunraysia Daily 1966 – 1974 reveals that this period was one of significant evolution in the tone and content of articles about Aboriginal people in the Sunraysia Daily. Over this period parts of Mildura’s non Aboriginal community rallied in support of Mildura’s Aboriginal community, Mildura’s Aboriginal community views were reported in the Sunraysia Daily, and issues relating to Aboriginal people became more prominent in the paper. That said, many significant historical issues of the period, such as the establishment of the Aboriginal Tent embassy in Canberra and the discovery of Mungo Man and Mungo Woman received very little coverage in the Sunraysia Daily. The only mention of the latter (which was front page news in Australia’s national newspapers) was in 1972 – it is reproduced on page 17 of this artwork publication.

To coincide with the launching of Mildura Palimpsest Biennale #9, 7500 copies of the artwork The Sunraysia Daily 1966 – 1974 were printed and distributed for free as an insert into the Sunraysia Daily on Friday 4 October, 2013.

INSET IMAGE lower left: Ricky Micthell and Mathieu Gallois "out at Mungo Lake. Ricky introduced me to some of his elders, so I could get their approval for my project, and he was kind enough to also drive out to Mungo with me to show me around. Ricky's niece did some of the research for the project - searching the mirco fish files at the Mildura library for articles".

Audience as communties of interest and potential participants in a meeting or conflict of interests.

Justyna Scheuring (PL/UK), “WE PLAY TONIGHT NO MORE SORROW” (3:11 minute edit) 26th of April, 2012, Colchester Arts Centre, UK; featuring the bands Dingus Khan and GULLS playing simultaneously to a hall full of people who are divided into two audiences only by a low, wire-fence / barrier. The project was supported by the Polish Cultural Institute in London.

JS: WE PLAY TONIGHT NO MORE SORROW performance was based on an idea of a meeting taking place between two different groups of people.

RG: How interesting that they (mostly?) stayed and watched / listened even though it must have been apparent from the outset that it would impossibly defy their original expectations for musical "enjoyment".

JS: Yes, it was also a surprise to me, I expected that a big group of people will leave. Now I am planning to make this project happen in Jerusalem, Nicosia, Berlin - in the divided cities or the cities that hold a memory of division. I am curious how people will respond to the barrier and each other in those places. When the music unites the experience of both crowds - the barrier is the only artificial thing in the space.... though we have an imprinted response to obey it. The double gig itself was very emotional to follow from initial confusion to a connection and both bands playing as one... It was really amazing and obviously doesn't mean that next bands taking part in WE PLAY TONIGHT NO MORE SORROW will connect similarly.

“Scheuring’s work aims to de-construct the illusion of stability in everyday social relations. Her works provide a testing ground, a possibility to venture into the unknown or to employ a critical resistance within a given situation. In ‘We Play Tonight No More Sorrow’ Scheuring’s constructed situation is ‘outside-of’ or ‘displaced’ from the usual, but also integrated and grounded enough into real life sociospatial relations not to be completely removed and abstracted, and this is where the challenge lies. The collaboration or participation lies in the choice to attend the concert, and to choose to stay or to leave throughout.” [Sophie Hoyle, “The Incidental Participant”, 2012, p.26.]

Engagement with communities of place at the moment of presenting the project to a public audience: Two Golden Garage projects by German artist Ines Tartler, curated by Rob Garrett.

Auto Garage: The Golden Garage Service 2009, Britomart development precinct carpark, Auckland, New Zealand in May 2009.

Berlin-based Tartler presented the project with the aid of a team of Golden Garage Service Attendants especially recruited for the project. During the project members of the public were invited to host a golden car cover (especially fabricated gold-coloured lamé car covers) on their car while they parked in the public car park at Britomart, in Auckland’s CBD. Patrons of the car park were invited (by the artist, accompanied by a pair of attendants) to ‘host’ one of the car covers on their own car while it was parked, and thereby they became part of the Auto Garage concept and project. Each person’s participation was documented and each received a memento of their involvement (including a photograph of them with their car and Auto Garage installed on their car and information about the artist and the project). The Auto Garage project took place over 11 days; was open to the public for 88 hours; involved the artists, curator and a team of 7 attendants; resulted in the direct participation of 88 members of the public (many accompanied by their friends and family); and was experienced online by more than 4,000 viewers.

Tartler’s project in Auckland, and that which took place 4 years later in Gdańsk, were about valuing ordinary people in public places; offering the gift of care (“we will look after, in fact, protect, your car while you are away / indoors”) and with a symbol of ultimate value: gold. In Auckland this created a playful and unexpected set of exchanges that disrupted the articulation of the place; in Gdańsk it re-activtated debate about the local effects of the collapse of investment companies (rather, one in particular that used the colour gold in all its promotional material) in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis.

These micro-disruptions of the articulation of place can be understood if we ask whether a downtown parking lot or a parking space in a residential street can considered to be a “place” or not. Here I am intrigued by what French anthropologist Marc Augé says about “place” and “non-place” in his 1995 book titled Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. [London: Verso.] If one defines "place" as "relational, historical and concerned with identity, then a space which cannot be defined as relational, or historical, or concerned with identity will be a non-place.” (p.78) “A person entering the space of non-place is relieved of his usual determinants. He becomes no more than what he does or experiences in the role of passenger, customer, or driver. . . . The space of non-place creates neither singular identity nor relations; only solitude, and similitude. There is no room for history unless it has been transformed into an element of spectacle, usually in allusive texts.” (p.103)

In the Auckland parking lot, people’s usual expectations a) going unnoticed other than the attention of ubiquitous surveillance; and b) having to pay for their time and space, were suddenly inverted: a) they were approached as individuals and engaged in dialogue involving a request to participate without strings attached; and b) their car, by coming under the “protection” of the golden cover stayed for free for as long as they wished to leave it there. These small gestures – conversation, an offer where they were truly free to choose, the gift of care and protection; and free time – all constituted powerful symbols of how things could be in public space. These gestures also transform the “non-place” albeit temporarily and ephemerally, into a “place,” that is as relational (strangers engaging with each other), historical (the event creates a site-specific memory) and concerned with identity (in that people are not engaged as friends, family or transactional subjects; but as someone whose opinion and choices are sought in the re-shaping of public space – if only temporarily).

Gdańsk Golden Garage, Pułkownika Jana Dziewanowskiego residential neighbourhood, Long Gardens, Gdańsk, November 2013; for "Unearthing Delights" the 5th edition of Narracje.

In Gdańsk the contingencies were different from those in Auckland. There the project took place in a small residential neighbourhood and the invitation to participate and the offer of “care” for their cars was made to those living in the street by the artist accompanied by one assistant in the early evening. In this district the project sought to engage ordinary private individuals in moments of public honouring. Here in Gdańsk the history of gold as a marker of value and private property especially, was tarnished by widespread anger over the collapse of a local investment company and the resultant loss of many people’s life savings during the recent Global Financial Crisis. The company had used gold and bullion as its advertising brand and its offices were only a few city blocks away from this neighbourhood. Given that the symbolic potential of gold is tarnished in this way, this project aimed to recuperate the colour for ordinary people through the gesture of conversation and the gift of symbolic care; and to create more positive local associations.

In preparing the programme for the 5th edition of Narracje it was important to remember, and to engage with the fact that this area of the city is “home” to many people; that it is not simply an “unmade” and neglected territory (as it could potentially be characterised). Therefore artists and curator met with residents during site visits to propose and encourage projects that might engage with residents in their day-to-day situations; and to accord such people the respect of offering opportunities for them to participate and even to answer back and to resist such art activities as we might introduce to the territory. The Pułkownika Jana Dziewanowskiego residential neighbourhood was selected as a site for community participation that responds to the motivations of making “home.”

During the course of the 3 nights of the Narracje festival, each of the 3 golden car covers was adopted by local residents to cover their cars between the hours of 5pm and midnight.

Les Nouveaux commanditaires / New Patrons is a well-established European model for local communities to be active initiators and decision-makers in the commissioning of public art.

How is the New Patrons different from public commissioning?

An artwork no longer solely originates from the personal needs of the individual creator, but also from the needs of society which is represented by people who agree to fully assume roles as decisive as those of artists.

Just as a government cannot legitimately define artistic content, neither does simply increasing the cultural offer meet the founding aim of democracy: allowing everyone to play a role in history, rather than remain spectators of an event of which they understand neither the origin nor the purpose.

After six centuries as the home of the creation and development of the revolutionary concept of the free and independent individual, an art scene led by New Patrons will enable us to build on this success to transform public life and adapt our perception of the world to the reality of its transformations.

Who can be a patron and what is requested of the artwork?

Anyone who wishes and agrees to take on the responsibility.

Nor is it necessary to be especially cultivated in order to have the desire to rebuild your relationship with the world when these upheavals affect your identity, history, relationships and environment.

Anyone can show intelligence and courage. Anyone can reflect on their own situation and find the right words to express themselves, to forge a dialogue with artists and to influence those involved in the realisation of a project that is about to become part of the life of a community.

In addition, artists do not like to be placed in competition, and asking several artists to bid with project ideas is a costly exercise. Avoiding this will greatly improve the quality of the creative work.

3 Steps:

Step 1: THE REASON FOR COMMISSIONING

You have an issue or problem that you share with your colleagues, neighbours or association members, and you believe an art project is the right way to make this public. You then contact your regional mediator, a renowned art curator. In conversations, she or he helps to formulate the content of the project. She or he arranges a meeting with an artist– from the discipline (fine art, architecture, design, music) which you will have chosen together – who is able to give form to your project.

Step 2: DIALOGUE WITH THE ARTIST

The artist develops a clear proposal in reference to the exchanges that have taken place with the mediator and the patrons.

Step 3: CREATION OF ARTWORK

With guidance from the mediator, you seek financial, governmental and political support for the project. The patrons, the artist and the mediator all remain involved until the completion of the project. You play an essential role in how the society receives it.

Link: Les Nouveaux commanditaires / New Patrons website.

Example illustrated above: A Place for Meditation and Prayer (1997-2000), Michelangelo Pistoletto and the Paoli-Calmettes Institute de Marseille.

Founded in 1925, The Paoli-Calmettes Institute is center for the fight against cancer. The hospital decided to reconstruct its chapel. A space where a symbolic organization would invite meditation and allow for the practice of all religions. View video.

'Local Initiatives' projects in Gdańsk which are examples of community self-expression projects co-authoried between community members and artists.

As an adjunct to the "Narracje 5" programme of site-specific projects commissioned from artists, a series of community self-expression projects was presented. These 'Local Initiatives' projects were sought through an Open Call within the defined geographical community defined by the territory of the "Narracje 5" festival. Projects were proposed by community members with or without the involvement of artists and presented together at a community meeting, where local residents selected which projects would receive the allocated Dom Kultury / Culture House funding and be approved for realisation. The main criteria for selection were that the project should target the residents of the district and engage them as co-authors. The projects were not required to be conceived as 'art' projects but more as community narratives, expressing locals' accounts of social history, contemporary lifestyle, relationships and so on. Nevertheless, several of the projects involved artists and all projects used aesthetic forms of one kind or another for their expression; such as photography, costume, model-making, theatrical workshops, installation and video.

Six projects were selected though this process and were integrated within the programme and trail of "Unearthing Delights" the 5th edition of Narraje in Gdańsk, Poland (November 2013).

'Local Initiatives' projects in Gdańsk which are examples of community self-expression projects co-authoried between community members and artists.

Top left: Joanna Stanisławek, “Awakening” 2013. This project was conceived by a local school girl who wanted to create a visual 'network' of the familial and social connections in her street. A net of strings and lamps was hung between, and connecting the windows and balconies on Seredyńskiego Street. The strings and lights refer to a form of communication most Gdańsk locals know from their childhood, called string mail. In this project residents of the street, the author`s neighbours were involved.

Top right: Katarzyna Hajduczenia and Justyna Halikowska, “The former, enchanted world of Długie Ogrody” 2013. This project introduced local children participants to the beauty and history of the distinctive Długie Ogrody area chosen as the focus area of the "Narracje" public art festival. The project gave children a chance to rediscover the charm of the territory. After an introduction to activities that took the form of an educational story-game based on the history of the district and of its people, children made a model of the city, recreating the old street layout. Live plants, planted during the workshop created a symbolic reference to the former “long gardens” function of the district. The project aimed to raise awareness and knowledge about the past and the fate of these areas and to develop eco-friendly attitudes and responsibility towards the children’s surroundings.

Centre right: Henryk Glaza and Paweł Seroka, "A Walk" [Spacer] 2013. The project arose out of discussions between the curator of "Unearthing Delights" and local residents during an early research visit to the Długie Ogrody area of Gdańsk in which the stories of growing up in the area merged with the stories of residents' grandparents settling the area in 1945-46 after the devastation of WWII. The project uses video interviews with locals who lead the camera on personal journeys around the neighbourhood; and presents the subjective history of the Długie Ogrody area though the on-camera remembered experiences of these local and former residents. The resulting video was projected in a backyard at 4 Seredyńskiego Street.

Bottom right and left: Joanna Kozera, "Dusting" 2013. In this project the Warsaw artist Kozera worked with local residents to create a platform for them to select, collate and present their personal and local organisations' photographic archives of the history of the Długie Ogrody area and of the lives of its residents over the past several generations. The photographs were suspended in the street windows of local cooperating businesses so that passersby could view the pictorial narratives (at 27, 21 and 11 Długie Ogrody Str.).

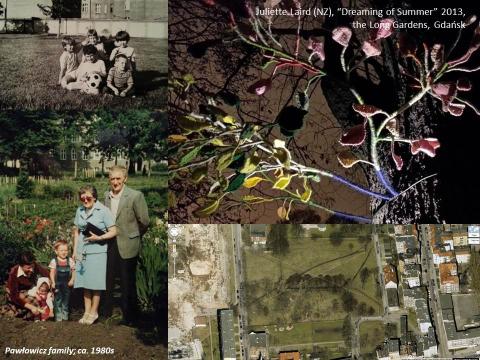

An example of a project in which there is both co-authoring with an 'ethnic community' and audience engagement to connect 'communities of place' with their own social history: Juliette Laird's site-specific installation “Dreaming of summer” (2013) commissioned by curator Rob Garrett for "Narracje 5" in Gdańsk, Poland.

The artist and concept were selected for "Narracje 5" by Rob Garrett for the potential to create an audience experience of delight and wonder that at the same time connected audience members with the contingencies of their time, specifically in relation to the 'lost' communal gardens of the area; and with the forgotten stories of local social history and Polish migration in the three generations since the devastation of WWII.

The project was intended to make the site resonate with an affective immediacy that would awaken in audience memebrs a desire to know more and connect with the site, its histories and its social uses, in order to make better sense of the present and to awaken their imagination for improved futures.

For the curator, the area's long history as a place of the people's gardens was singularly important; especially in this site which is the only formal public 'green space' in the whole Dlugie Ogrody territory; a part of which, as recently as the 1980s, was used by local families for their vegetable and flowers gardens and groves of fruit trees and then mysteriously the allocations were removed by the state.

For the artist, the story of Polish children being sent to New Zealand in 1944 to protect them from the hardships of war, became the catalyst for engaging with these (now grown) 'Pahiatua children' as they are known in New Zealand. The artist worked directly with the Polish emigres and told their story through her installation; as well as the wider, more universal story of people trying to graft themselves onto new homes.

The relatively recent re-settlement of Gdańsk gave this project added poignancy and also for locals it became the catalyst for learning about unfamilair or unknown aspects of their neighbourhood's history. With the almost total destruction of Gdańsk in 1945 - bombed first by the British and then over-run by the Russians as they swept westwards towards Germany - and the largely German population fleeing, the city was left at the end of World War II more-or-less empty and almost uninhabitable. Nevertheless people gravitated towards the few buidlings left standing and the partial ruins for even more impoverished places left desolate by the war, from rural areas of Lithuania, Poland and the Ukraine; and they began to make home. Laird's project was situated in one of the few areas of Gdańsk where there buildings that families settled to begin their new lives; and some of the local residents today who grew up in the neighbourhood remember the stories their grandparents told of those early days of patching together homes and lives out of the ruins.

Thus Laird's idea about the Polish children sent to New Zealand 'grafting onto new places' had a double resonance for the children and grandchildren of those who re-settled the neighbourhood of Długie Ogrody in 1945 and 1946.

An example of a project in which the audience is engaged as a 'local community' through the commentary of guided tours which aimed to connect people to the social history of the site and to their personal experiences of remembering through the encounter with the performance-video project "Silencio" by French artist Alexandra Guillot.

"Silencio" was commissioned by Rob Garrett for the 5th edition of Narracje in Gdańsk, Poland (November 2013). The artist is located in the basement of the building shown, where she is being filmed as she sits at a small table methodically and slowly feeding sheets of white paper into the paper shredder in front of her. A mountain of paper strips accumulates in front of the table. This scene is projected in a live video-feed onto the exterior of the apartment building.

The suggestion of the paper-shredding is that the artist might be reading a document before shredding it… What is she doing? Reading to remember? Shredding to forget? The paper-borne story is like the voice of the story-teller: it exists in the ears for a fleeting moment and can only live on in the listener’s memory and in their own re-telling of the story. To be somewhere and perfectly well know that soon the sensation of being there shall disappear, to want to keep holding it against you, to want it to pierce you.... [Alexandra Guillot]

This project was selected for its evocation of the uncertain relationship between experience and memory; and the site of the project was selected for its historic association with the lost voices, stories and memories of former occupants of the polder (wetlands) of this part of Gdańsk right up to the start of the 20th century.

Many of the current residents of Gdańsk, and those who joined the guided tours around the "Narracje 5" projects are the decendents of Lithuanian, Ukrainian and Polish villagers who re-settled the empty and destroyed city from 1945 onwards. They form the local community and yet their connection to the social history of the city is fragmented and disjointed. The "Silencio" project combined with the commentary of the guided tours (which talked about the social history of the site) aimed to connect audience members to the 'forgotten' social and thus constitute them as a community of place.

The particular lost voices, dialects, peoples and stories could be heard in this district almost till the end of the 19th century when the place now known as Pułkownika Jana Dziewanowskiego became a street. Prior to that it was one of the waterways that criss-crossed the Długie Ogrody polder; and served a dual purpose of draining the flat land and providing inland access to river craft. Guillot’s “Silencio” project became a catalyst for stories of the lost dialect and songs of the Flisacy, the Vistula raftsmen, street traders, craftsmen and entertainers who travelled to and from, and occupied this place, for many centuries.

The fact that anything much is known about the lost dialects and songs of the 18th century Vistula Rafters and Gdansk Pedlars owes much to an 18th century publication which set out to record them, and this a good century before the development of professional collecting of folk music and the study of folklore. In 1762-1765, an engraving workshop in Gdansk belonging to M. Deisch (1724-1789) published a cycle of 40 etchings known today as 'Die Danziger Ausrufer' (The Gdansk Criers). The etchings show street traders, craftsmen and entertainers, and the texts of the verbal and musical cries of these pedlars in a notation that is close to the living original encountered in the streets. The author of the musical record (who may have been Kunegunda Czacka, an aristocrat and a talented promoter of art) tried to record with precision the significant differentiation in the rhythm, the temporal progress of the cries, and even attempted to record the movements of the criers, also using non-standard signs. While recording the cries in musical notation may have caused them to be smoothed out to some extent; it is because they were recorded and published at all that we now have an approximate picture of the cries of Gdansk itinerant traders. [Source: Abstract of Brzezinska B., “The Cries of Itinerant Traders of Gdansk (1762-1765)” published in Muzyka (Music), the journal of the Institute of Art, Polish Academy of Sciences; 2005, 50: 2(197), pp45-77.]

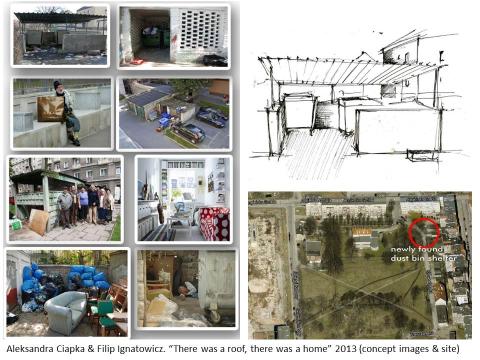

An example of a co-authored project between artist duo Aleksandra Ciapka and Filip Ignatowicz (PL) and the residential community of Krowoderska street and Angielska Grobla in the Długie Ogrody / Long Gardens district of Gdańsk, Poland.

“There was a roof, there was a home” was an ambitious concept submitted as part of an Open Call to Polish artists in the development of the "Narracje 5" programme. The artists proposed to identify and work with a residential community within the "Narracje 5" territory in order to firstly gain permission to take over and transform a communal dust-bin collection area as their site; and secondly to invite members of the local community to co-author the project with them in order to make the site a place for their own expression of what it means to create a "home". The artists proposed a platform, a stage; and the project did achieve the participatory goals the artists set themselves at the outset.

Project: “There was a roof, there was a home”, installation of donated and found furniture, domestic items and personal belongings in a community dust-bin area (15-17 November 2013); developed for "Unearthing Delights" the 5th edition of "Narracje - Installations and Interventions in Public Space", Gdańsk, Poland; curated by Rob Garrett.